This is a guest post from Kurt Opsahl, Deputy Executive Director and General Counsel of the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

October is National Cyber Security Awareness month and Rapid7 is taking this time to celebrate security research. This year, NCSAM coincides with new legal protections for security research under the DMCA and the 30th anniversary of the CFAA - a problematic law that hinders beneficial security research. Throughout the month, we will be sharing content that enhances understanding of what independent security research is, how it benefits the digital ecosystem, and the challenges that researchers face.

It's been thirty years since Congress enacted the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the primary federal law to criminalize hacking computers. Since 1986, the CFAA has been amended many times, most often to make the law harsher and more expansive.

While it was written to focus on what were then relatively rare networked computers, the ubiquity of the Internet means today that almost every machine more useful than a portable hand held calculator is a “protected computer” under the law.

As the anti-hacking law's scope expanded, so did the penalties. Today there is little room for hacking misdemeanors under the CFAA. Even where there is, there's virtually no crime that can't be upgraded to a felony by an aggressive U.S. Attorney through the simple expedient of tying the crime to a parallel state law. This ends up meaning that you might get sentenced to community service for vandalizing a printed billboard, but endure two years in prison for vandalizing a Web page.

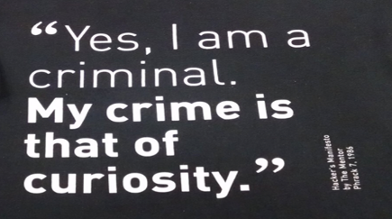

There are many problems with the CFAA and its interpretation. The Department of Justice has used the anti-hacking law to criminalize violations of Terms of Service or iterating a URL. But one problem stands out: the over-criminalization of curiosity.

A few months before the CFAA originally passed, the e-zine Phrack published the The Hacker Manifesto, in which The Mentor explained to the world his crime: curiosity. The Mentor, a hacker affiliated with the Legion of Doom, celebrated exploring and outsmarting, discovering a “door opened to a world” beyond the mendacity of the day-to-day.

Over the years of working on the EFF's Coders' Rights Project, we've had the honor of representing many smart and skilled security researchers, who've made considerable contributions to our collective security.

We won't be naming names, but at least a few of these luminaries got their start in computer security from curiosity, figuring out at a young age how the machines in their lives worked, and how to make those machines work in unexpected ways. An intellectual adventure, but one fraught with the risk that these unexpected ways could cross the line into “access without authorization,” and then felony charges.

Perhaps the clearest example of the danger of criminalizing curiosity comes from the prosecution of Aaron Swartz. In 2011, a federal grand jury in Massachusetts charged Aaron Swartz with multiple felonies for his alleged computer intrusion to download a large number of academic journal articles from the MIT network.

Swartz was instrumental in the development of key parts of modern technologies, including RSS, Creative Commons, and Reddit, getting his start at an early age. He was just 14 when he joined the working group that authored RSS 1.0. Yet for his curiosity, Swartz was facing a maximum sentence of decades in prison. Realistically, he would have had to serve less time, but even so he would have been saddled with felony convictions forever. Instead, Swartz took his own life, and the world lost a bright star could have continued to bring great things to the Internet.

Paul Allen and Bill Gates provide the counterexample. In his autobiography, Allen told the story of when the two founders of Microsoft “got hold of” an administrator password at the Computer Center Corporation (which they called C-Cubed), a company that provided timeshare computers to the pair.

With the cost of access mounting, eighth grade Allen and Gates wanted to use the password to give themselves free access to the timeshare servers. However, C-Cubed discovered the hack. As Allen explained:

“We hoped we'd get let off with a slap on the wrist, considering we hadn't done anything yet. But then the stern man said it could be ‘criminal' to manipulate a commercial account. Bill and I were almost quivering.”

But instead of calling the police, Dick Wilkinson, one of C-Cubed's partners, kicked them off the system for six weeks, letting them off with a warning. Eventually, C-Cubed exchanged free computer time for bug reports, allowing the kids to play and learn, so long as they carefully documented what led the computer to crash.

Computer security will always be difficult, and protecting our networks and devices requires the hard work of skilled security researchers to find, publish and fix vulnerabilities. The skills that allow security researchers to discover vulnerabilities and develop proof of concept exploits are often rooted in satisfying their curiosity, sometimes breaking some rules along the way.

Society may still want to discourage intentionally destructive behavior, and hold people accountable for any harm they may have caused, but certainly not every hack needs to be a felony, backed by stiff sentences and they lifelong encumbrances that come with being a felon. By allowing for infractions and misdemeanors, coupled with recognition that a little mischief may be an early sign of someone who will be vital to protecting us all.

Kurt Opsahl is the Deputy Executive Director and General Counsel of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. In addition to representing clients on civil liberties, free speech and privacy law, Opsahl counsels on EFF projects and initiatives. Opsahl is the lead attorney on the Coders' Rights Project, and is representing several companies who are challenging National Security Letters. Additionally, Opsahl co-authored "Electronic Media and Privacy Law Handbook." Follow Kurt at @kurtopsahl and the EFF at @eff.