by Bob Rudis, Tod Beardsley, Derek Abdine & Rapid7 Labs Team

What do I need to know?

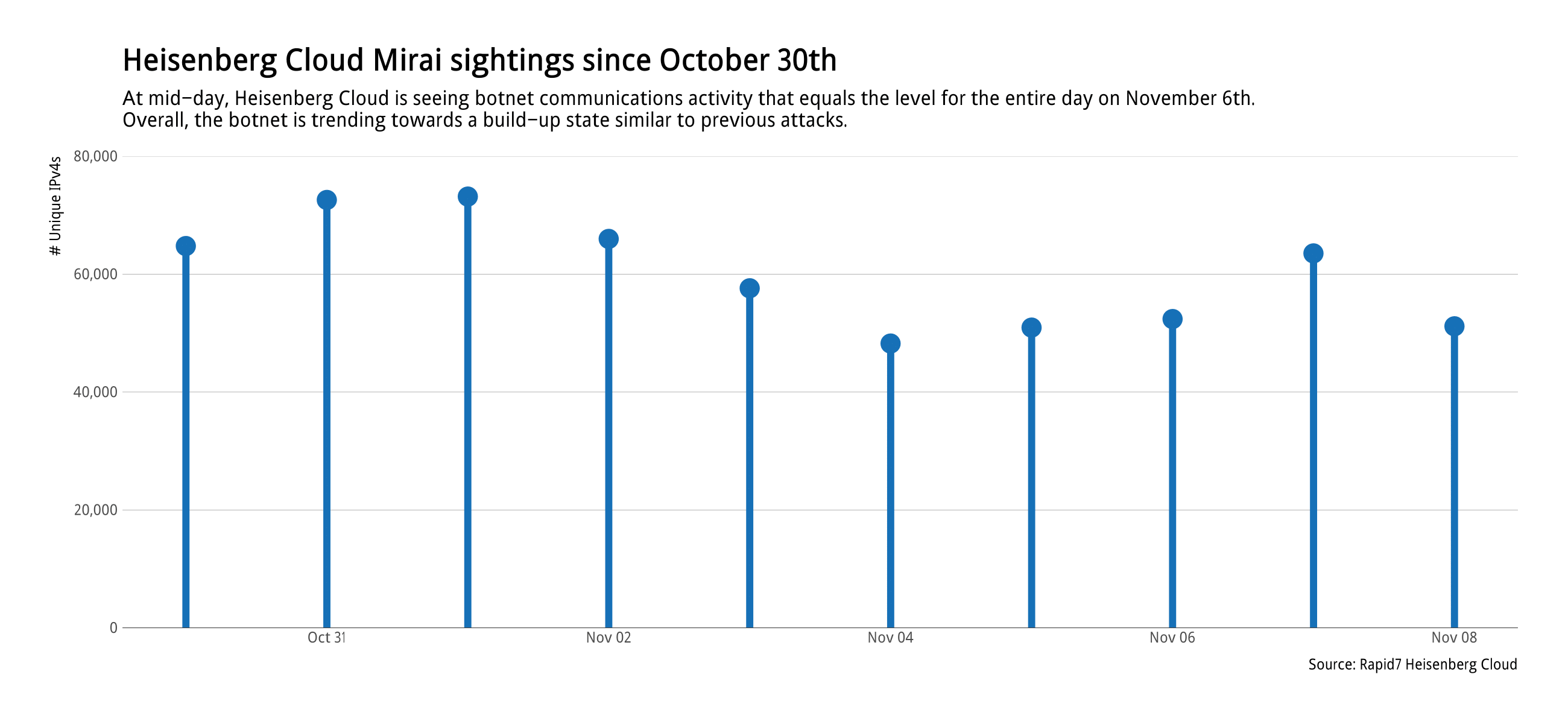

Over the last several days, the traffic generated by the Mirai family of botnets has changed. We've been tracking the ramp-up and draw-down patterns of Mirai botnet members and have seen the peaks associated with each reported large scale and micro attack since the DDoS attack against Dyn, Inc. We've tracked over 360,000 unique IPv4 addresses associated with Mirai traffic since October 8, 2016 and have been monitoring another ramp up in activity that started around November 4, 2016:

At mid-day on November 8, 2016 the traffic volume was as high as the entire day on November 6, 2016, with all indications pointing to a probable significant increase in botnet node accumulation by the end of the day.

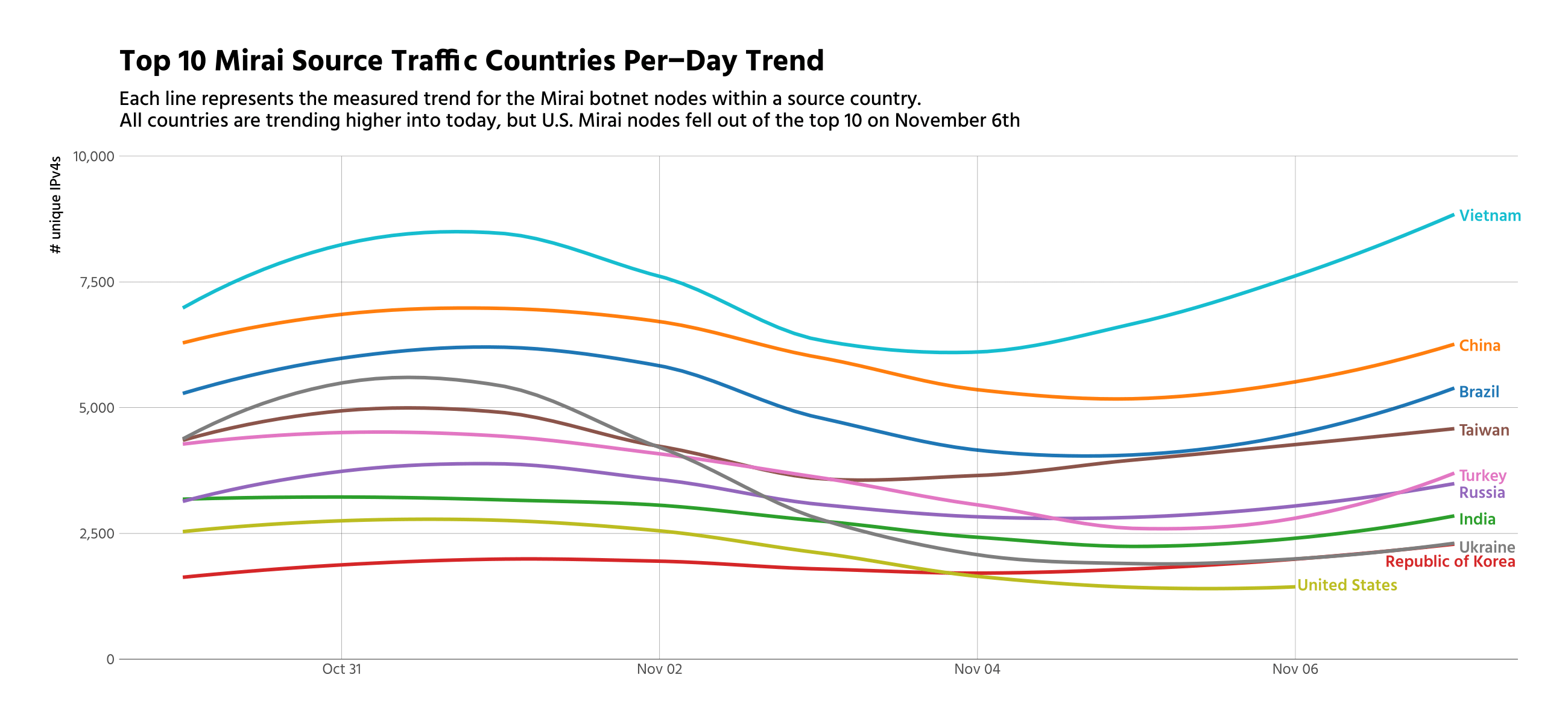

We've also been tracking the countries of origin for the Mirai family traffic. Specifically, we've been monitoring the top 10 countries with the most number of Mirai daily nodes. This list has been surprisingly consistent since October 8, 2016.

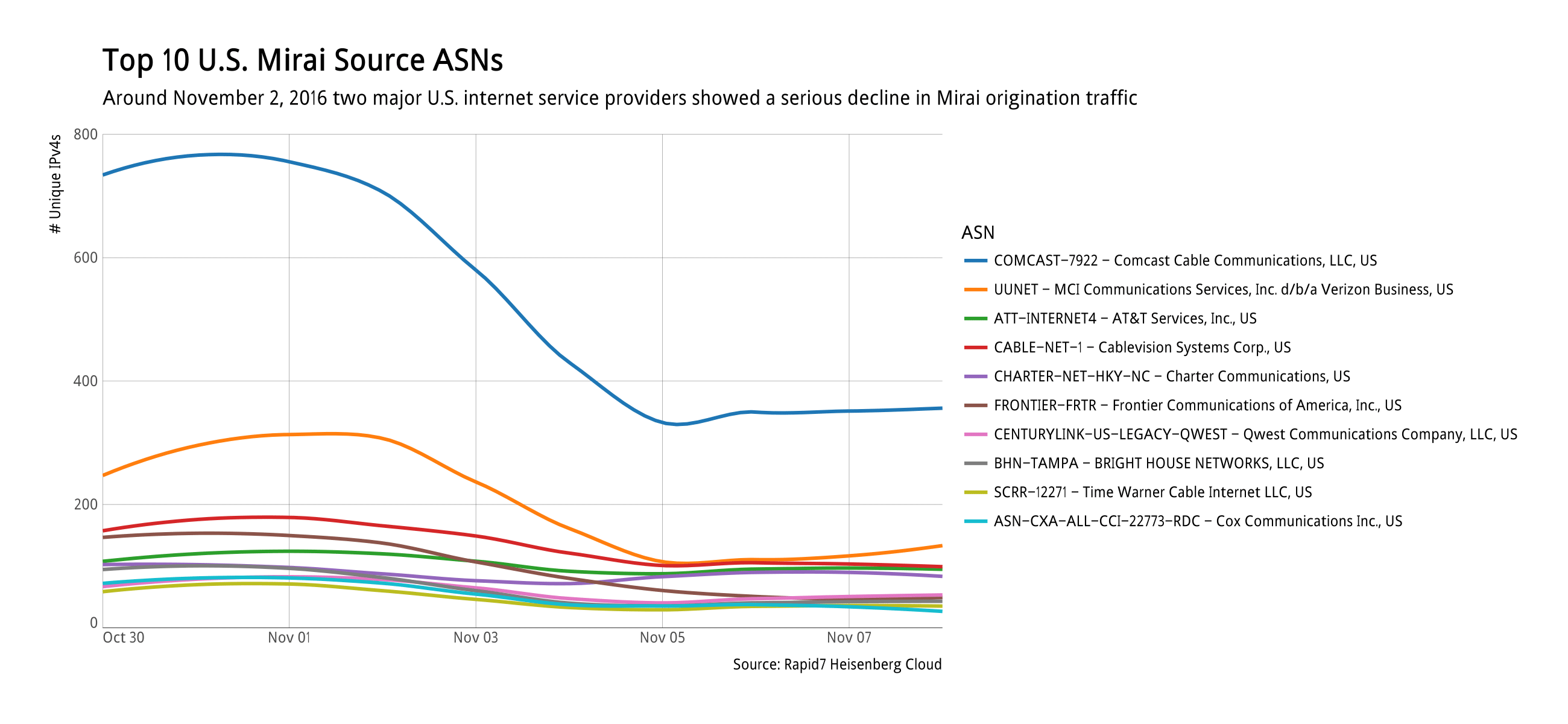

However, on November 6, 2016 the U.S. dropped out of the top 10 originating countries. As we dug into the data, we noticed a significant and sustained drop-off of Mirai nodes from two internet service providers:

There are no known impacts from this recent build up, but we are continuing to monitor the Mirai botnet family patterns for any sign of significant change.

What is affected?

The Mirai botnet was initially associated with various components of the “internet of things”, specifically internet-enabled cameras, DVRs and other devices not generally associated with malicious traffic or malware infections. There are also indications that variants of Mirai may be associated with traditional computing environments, such as Windows PCs.

As we've examined the daily Mirai data, a large percentage of connections in each country come from autonomous systems — large block of internet addresses owned by the provider of network services for that block — associated with residential or small-business internet service provider networks.

How serious is this?

Regardless of the changes we've seen in the Mirai botnet over the last several days, we still do not expect Mirai, or any other online threat, to have an impact on the 2016 United States Presidential Election. The ballot and voting systems in use today are overwhelmingly offline, conducted over approximately 3,000 counties and parishes across the country. Mounting an effective, coordinated, remote attack on these systems is nigh impossible.

The most realistic worst-case scenarios we envision for cyber-hijinks this election day are website denial of service attacks, which can impact how people get information about the election. These attacks may (or may not) be executed against voting and election information websites operated by election officials, local and national news organizations, or individual campaigns.

If early voting reports are any indication, we expect to see more online interest in this election than the last presidential election, and correspondingly high levels of engagement with election-related websites. Therefore, even if an attack were to occur, it may be difficult for website users to distinguish it from a normal outage due to volume. For more information on election hacking, read this post.

How did we find this?

We used our collection of Heisenberg Cloud honeypots to capture telnet session data associated with the behaviour of the Mirai botnet family. Heisenberg Cloud consists of 136 honeypot nodes spread across every region/zone of six major cloud providers. The honeypot nodes only track connections and basic behavior in the connections. They are not configured to respond to or decode/interpret Mirai commands.

What was the timeline?

The overall Mirai tracking period covers October 8, 2016 through today, November 8, 2016. All data and charts provided in this report use an extract of data from October 30, 2016 through November 8, 2016.