This blog was previously published on blog.tcell.io.

I’ve previously written about the Ticketmaster breach, which was the work of Magecart, a group that has been active since 2016. One of their latest victims was British Airways, which announced that it had been breached on Sept. 7, 2018 (remember that date, because it will be important later on).

Magecart's techniques are sophisticated and worth understanding in detail, especially because they point out a major gap that occurs even with perfect PCI compliance. PCI is focused on servers, an approach that made sense in the past: When an application is self-contained and monolithic, protect the application. However, applications today run both on servers and within the browser, and securing against browser attacks is, well, hard.

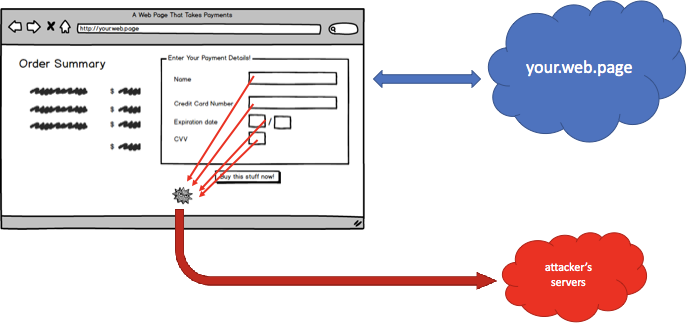

So, on to the British Airways breach. Magecart embedded just 22 lines of JavaScript into the British Airways web page. Scripts running in the browser can do anything. For this breach, the script was programmed to collect payment information fields when a button was clicked (or a touch event ended, just to be sure to get anybody on a mobile device) and bundle that information up to the attacker's services. To camouflage the breach, the attackers used the domain baways.com (registered with privacy protection, of course!), so any tools that reported third-party access would have a similar-ish-looking domain and might sneak in under the radar. They even bought an SSL certificate so that the browser wouldn't throw errors for mixed content.

PCI has a long list of requirements for security, many of which made sense when applications were developed as standalone monolithic code. British Airways was fully compliant with requirements, such as "don't store CVVs." Attackers obtained payment details by compromising end users' browsers—an environment that the airline has no control over.

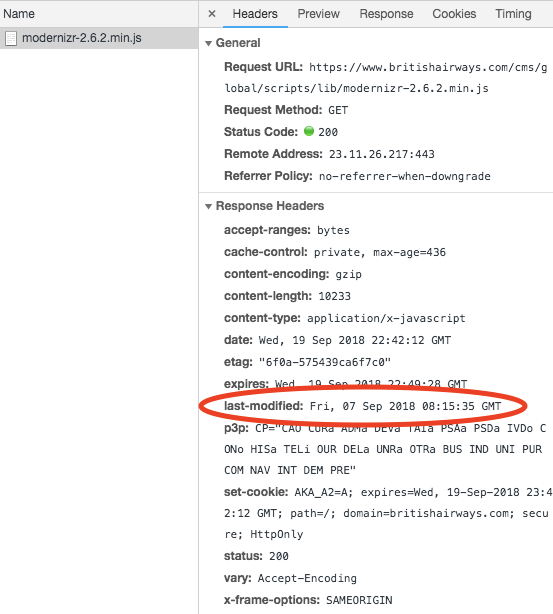

The attack was probably first noticed when malicious script was first detected. The script in question, modernizr-2.6.2.min.js, had a timestamp of 2012. When it was "updated" to include the malicious code, it received a new timestamp from Aug. 21, 2018. The rogue domain used by the attackers to collect information was registered on Aug. 16. These all point to a sophisticated attack in which attackers were able to modify a script on the British Airways website, then register a domain for the specific purpose of collecting data. Once the malicious stamp was detected, of course, the script received a new timestamp. Out of curiosity, I checked it while writing this post. The date? Sept. 7, the day British Airways announced the breach and presumably removed the malicious code:

What can you do about these attacks? Check out our post on defending against Magecart with CSP.