Windows Server 2008 and 2008 R2 reached their end of life (EOL) on Jan. 14, 2020. What does that mean in practice? Well, any instances running these versions of Windows Server are no longer supported by Microsoft—no more automated fixes, updates, or technical assistance.

From a security standpoint, any exploits that appear after Jan. 14 that affect these specific versions of Windows will not likely be addressed for the vast majority of installations. Though there have been exceptions to end of support under unusual circumstances, such as the extension of support for Windows 10 in light of the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, such exceptions shouldn’t be expected to be the norm.

Through a sampling of some of our data, we realized that even as of the date of this post, there were many instances of Windows Server 2008 still running in the wild—and by extension, associated variations of dependent software, such as Microsoft Internet Information Services (IIS) version 7.0 and 7.5.

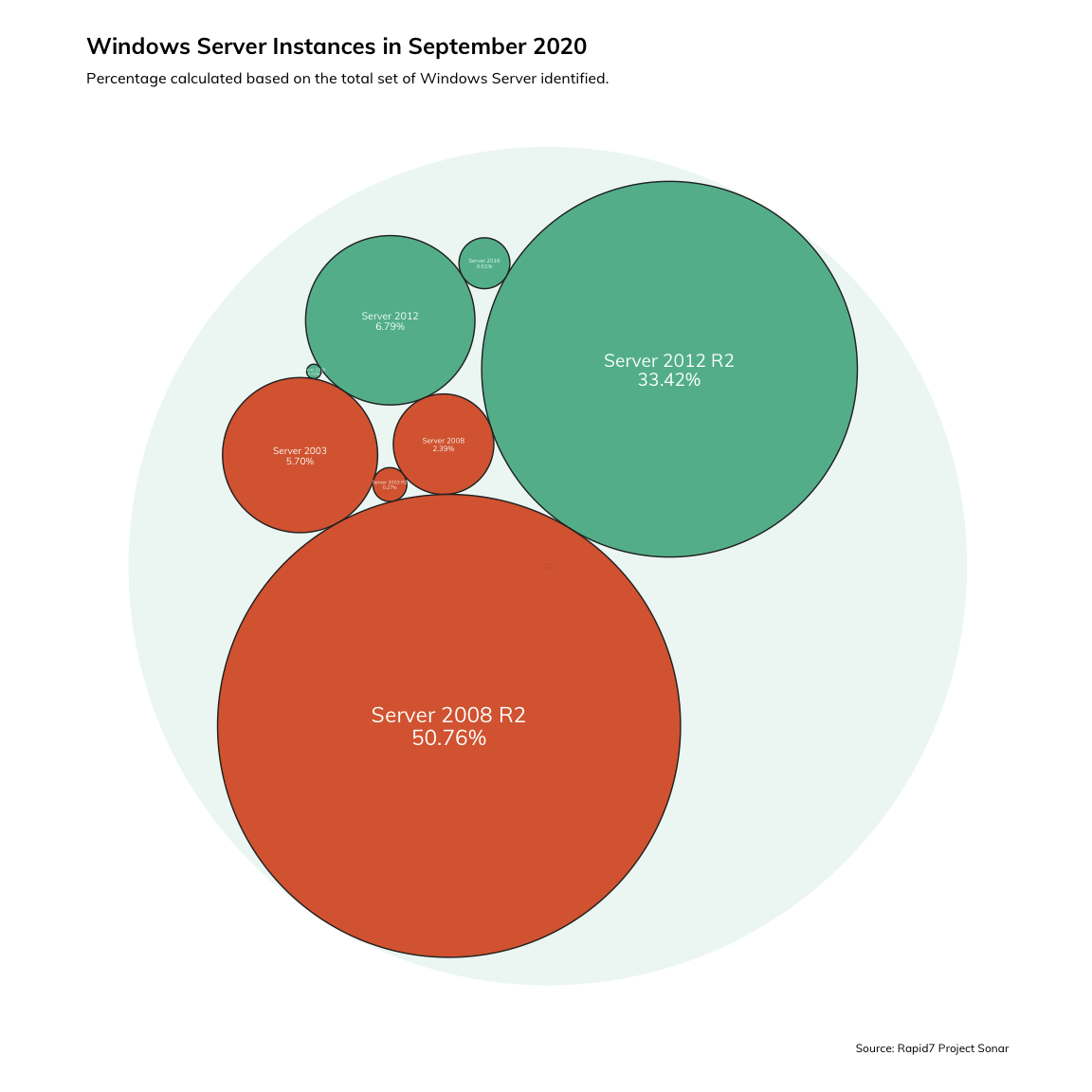

We took a more systematic look at the prevalence of the different versions of Windows Server that are floating out on the open internet. We performed a number of internet-wide scans using Project Sonar, and fingerprinted the returned data using Recog, when possible, to enable us to identify specific versions of Windows Server.

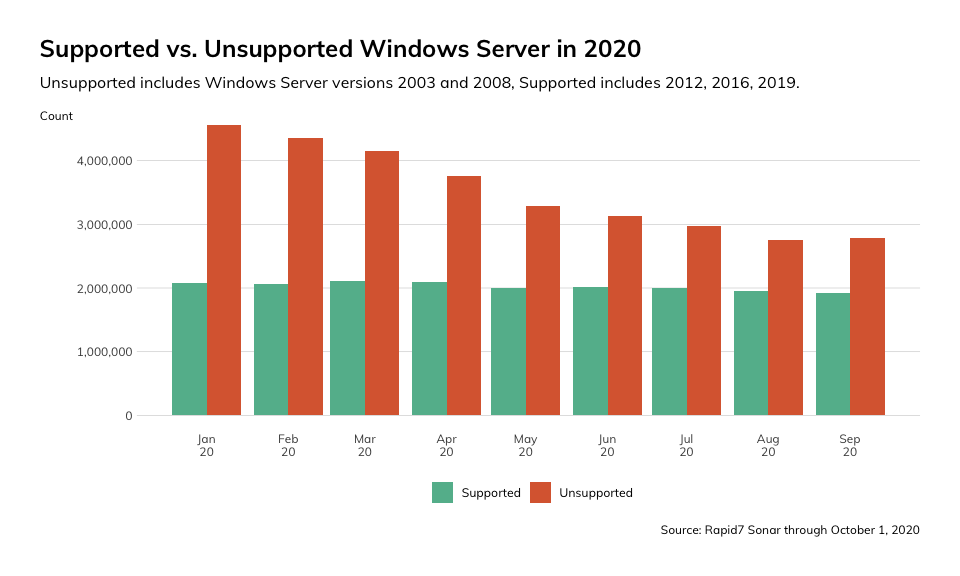

What we found was alarming: Over the course of September 2020, 59% of all uniquely observed instances of Windows Server were unsupported, while 41% were supported. However, the uneven balance of dangerous versus safe services that we observed is not terribly unusual. It seems to be more the norm that the preponderance of actively running services on the internet are outdated, unsupported, improperly patched, or insecure. For examples, see any number of Rapid7’s past blog posts, including reflections on the state of PHP and Microsoft Exchange.

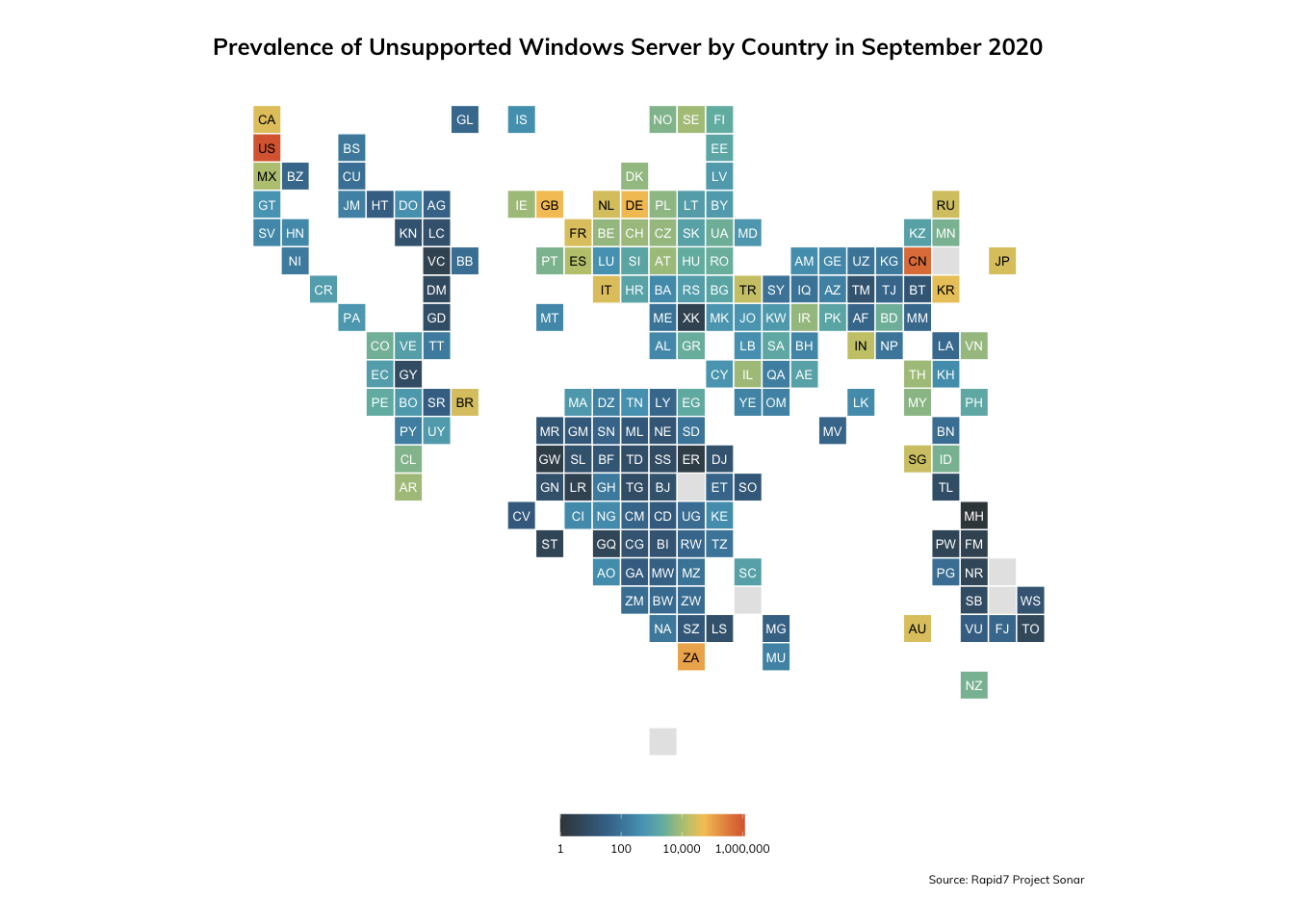

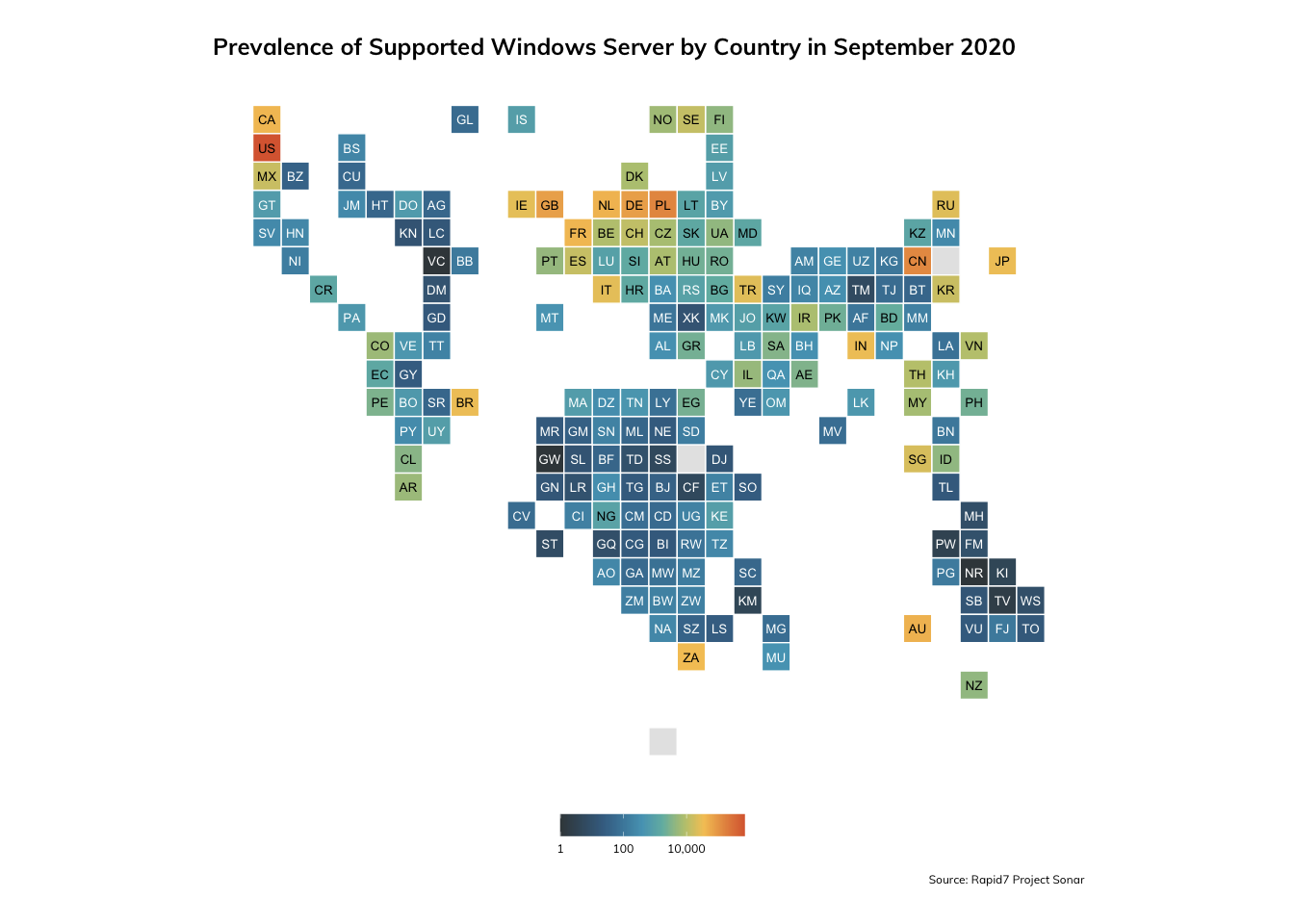

We were also able to identify the countries in which these unsupported Windows Server instances were located, and determined (without much surprise) that the heaviest concentrations were in the United States and China.

On the other hand, the heaviest concentrations of supported versions of Windows Server were also the United States and China, though if we examine the coloration scale more closely, we do see that the numbers for unsupported versions are significantly larger than supported.

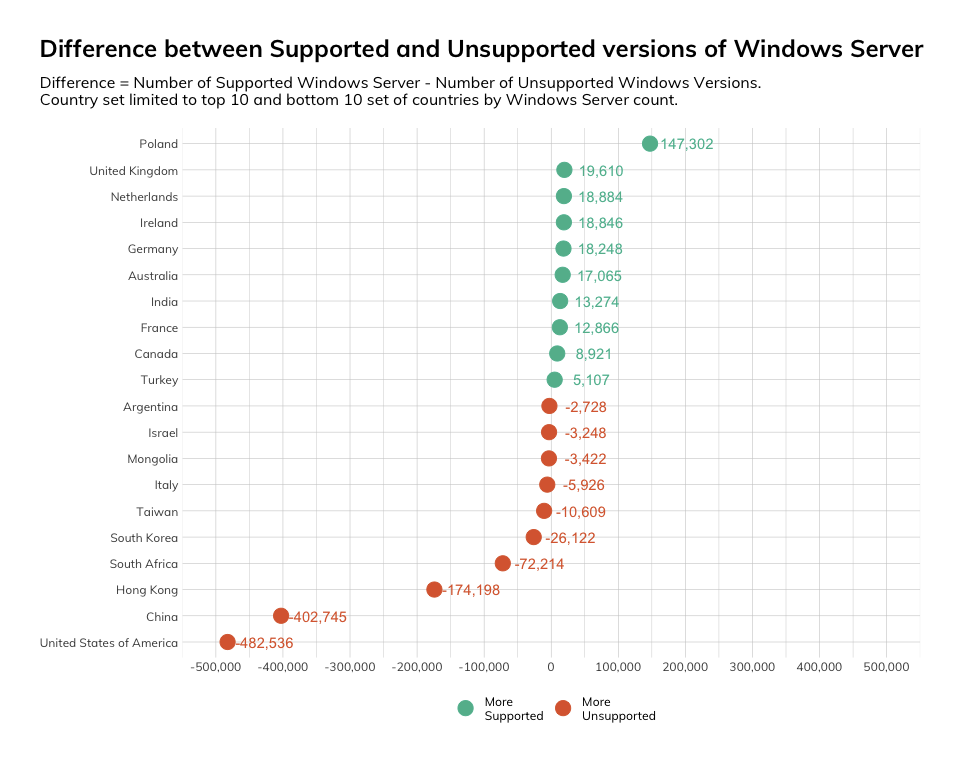

For a more direct comparison of supported versions of Windows Server against unsupported versions within countries, we calculated the difference between the two classes within each country. This allowed us to get past a consideration of the raw prevalence of Windows Server within particular countries. In this case, we found that Poland manifested itself particularly well, with the most dramatic difference in terms of absolute counts of supported over unsupported versions, while the United States appeared the worst off, with nearly half a million more instances of unsupported versions than supported.

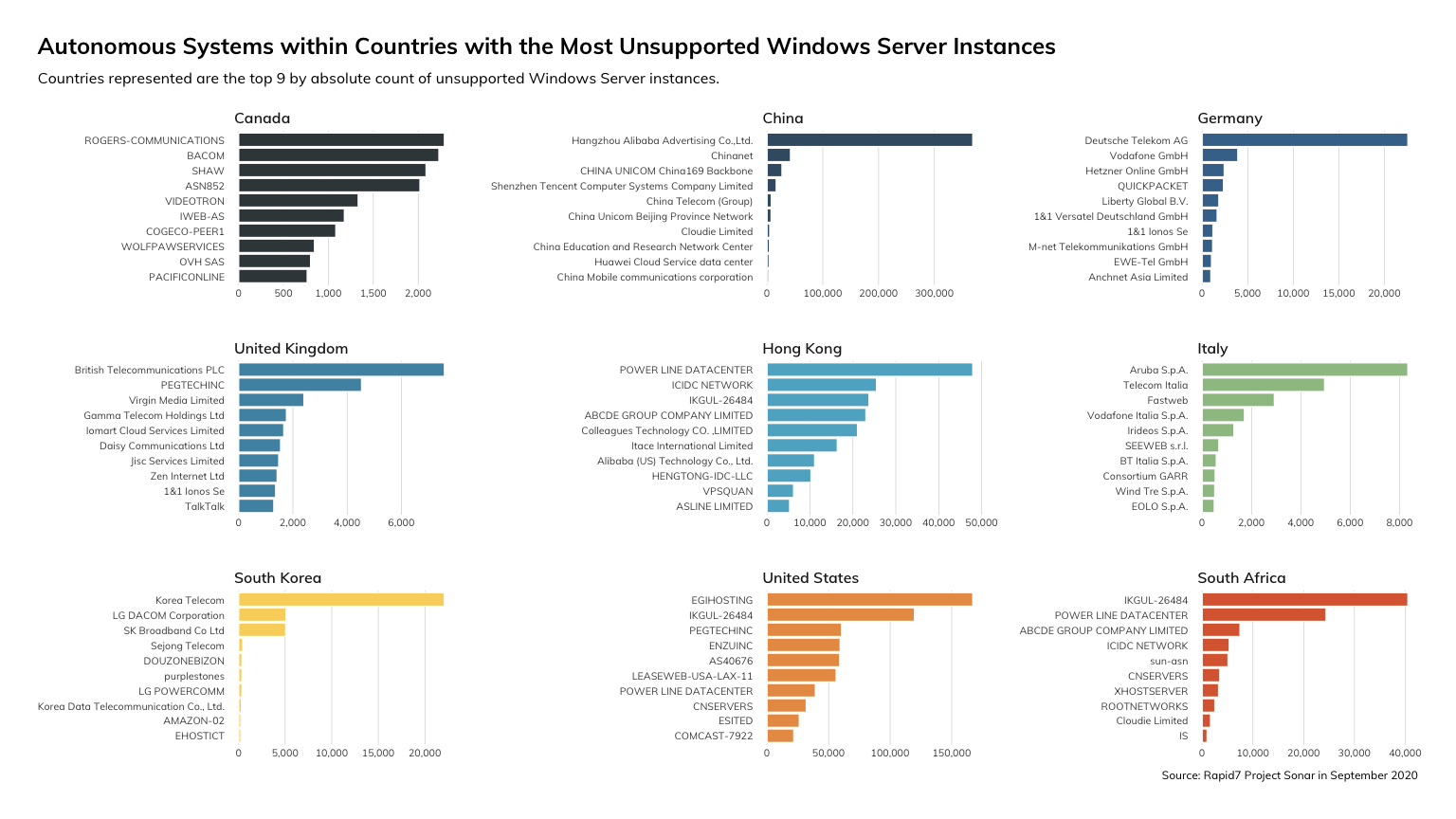

There is also observable variation between hosting service providers within countries in terms of unsupported Windows Server instances. For instance, we can note that Hangzhou Alibaba Advertising hosts by a wide margin the most instances of unsupported Windows Server instances within China.

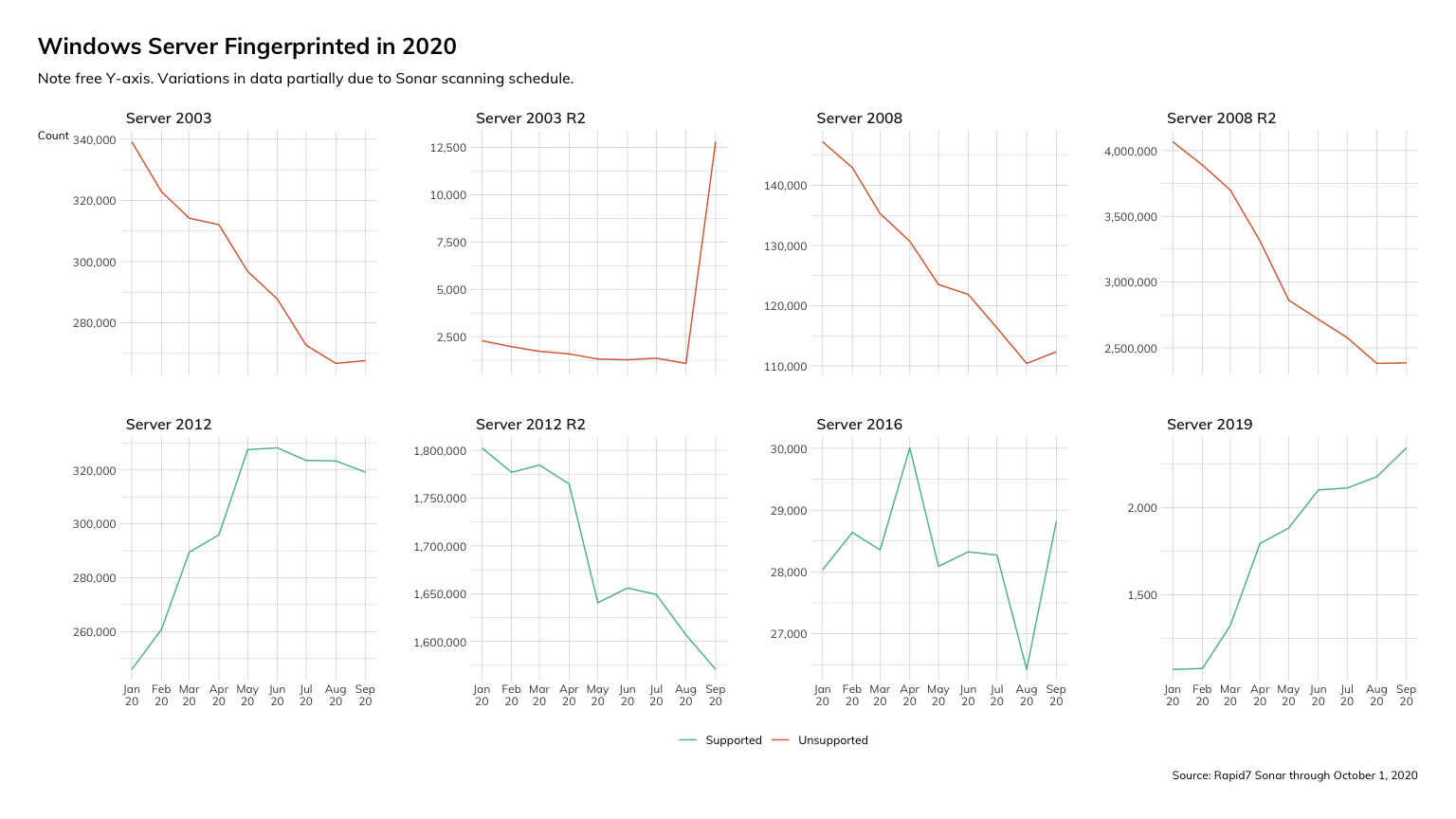

While we can assert that the state of Windows Server security across the internet in this latest month doesn’t look great, there does appear to be some level of progress. Over the past several months, we have observed a notable decline in the number of unsupported variants of Windows Server - including Windows Server 2003, 2008, and their various release candidates.

The decline in usage of Server 2008 and Server 2008 R2 amounted to approximately 40,000 and over 2,000,000 instances, respectively. The net decline that we observed in Windows Server instances does comport with what other internet researchers have observed as well. For instance, Netcraft noted a shift from Windows web servers to OpenResty. There was an unusual spike in counts (though not terribly significant in terms of absolute numbers) for Server 2003 R2 that we noticed and are still looking into, though at this time, our best guess is this is simply a manifestation of the somewhat stochastic spirit of Sonar.

How severe is all this? Well, it really depends on the types of vulnerabilities and exploits that crop up and how Microsoft decides to respond.

For instance, in early September, the Zerologon (CVE-2020-1472) vulnerability was publicly disclosed, with a whopping CVSSv3 rating of 10.0 (i.e., as bad as it gets). This allowed for the elevation of privileges up to a domain admin level by exploiting a cryptographic weakness in the Netlogon Remote Protocol. The vulnerability affected a number of versions of Windows Server. Microsoft addressed the Netlogon vulnerability with a round of patches in August, which fortuitously included a patch for Windows Server 2008 R2 SP 1 (based on the information released and some testing by Rapid7 Principal Security Researcher Tom Sellers, it seems that Windows Server 2008 is not susceptible to Zerologon).

Without the good graces of Microsoft, the Zerologon vulnerability could have become a perpetual vulnerability for millions of Windows Server 2008 R2 instances that remain open on the public internet. Imagine the prospecting opportunities for malicious actors yearning for domain admin access to critical enterprise production systems. Quite frankly, given the recency of the patch and the tendency for patches to be slow in application, it wouldn’t be surprising at all if there are many extant Windows Server 2008 instances that remain unpatched and severely exploitable, presenting ripe opportunities for mayhem.

Here are some key actions that can be performed to minimize the risk posed by the usage unsupported Windows Server versions:

- Stop using unsupported Windows Server versions. Migrate to a more recent and active version of Windows Server (or, if you are to follow Microsoft’s advice, simply migrate to the cloud and embrace Microsoft Azure).

- Remove public access to unsupported versions of Windows Server.

- If there remains a need to continue using unsupported versions, at the very least, apply past available patches. This doesn’t fully address the concerns manifesting from using unsupported versions, such as newly discovered zero-day exploits, but it does at least mitigate some past lingering risks.

NEVER MISS A BLOG

Get the latest stories, expertise, and news about security today.

Subscribe