Welcome to the NICER Protocol Deep Dive blog series! When we started researching what all was out on the internet way back in January, we had no idea we'd end up with a hefty, 137-page tome of a research report. The sheer length of such a thing might put off folks who might otherwise learn a thing or two about the nature of internet exposure, so we figured, why not break up all the protocol studies into their own reports?

So, here we are! What follows is taken directly from our National / Industry / Cloud Exposure Report (NICER), so if you don't want to wait around for the next installment, you can cheat and read ahead!

NTP (123)

In the immortal words of The Smiths, “How soon is now?”

TLDR

- WHAT IT IS: Network Time Protocol—the service that keeps us all in sync.

- HOW MANY: 1,638,577 discovered nodes. 1,638,495 (99.9%) gave up version and/or other fingerprintable information and (much) smaller subsets provided operating system information.

- VULNERABILITIES: A few. Mostly denial-of-service and information disclosure, but there have been remote code execution ones from time to time.

- ADVICE: Use it! Just not on the internet. And, configured properly. And, patched.

- ALTERNATIVES: Nope. This is the de facto way to keep time on the internet.

- GETTING: Stuck in time. There was literally no change from 2019.

The internet could not function the way it does without NTP. You’d think with that much power NTP would be all BPOC and act all smug and superior. Yet, it does it’s thing—keeping all computers that use it in sync, time-wise—with little fanfare, except when it’s being used in denial-of-service attacks. It has been around since around 1985, and while it is not the only network-based time synchronization protocol, it is The Standard.

NTP servers operate in a hierarchy with up to 15 levels dubbed stratum. There are authoritative, highly available NTP servers we all use every day (most of the time provided by operating system vendors and running on obviously named hosts such as time.apple.com and time.windows.com).

Virtually anything can be an NTP server, from a router, to your phone, to a RaspberryPi, so dedicated appliances that key off of GPS signals as a time-source. Now, just because something can be a time server does not mean it should be a time server.

Discovery details

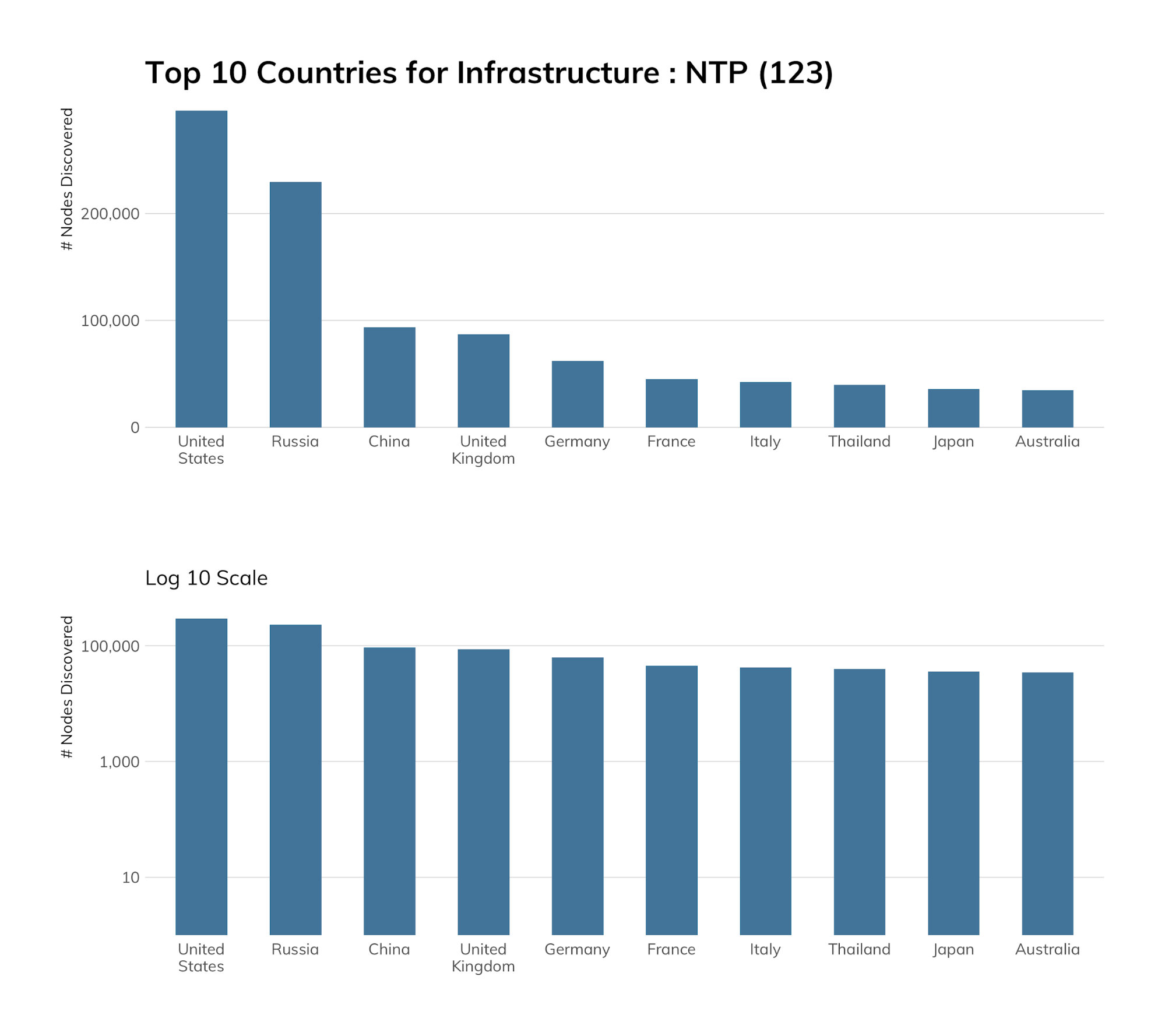

Project Sonar found 1,638,577 NTP servers on the public internet, so one might say we have quite a bit of time on our hands. Our editors say otherwise, so let’s see what time looks like across countries and clouds.

The United States has many IPv4 blocks, many computers, and many major ISPs and IT companies that like to control things. It also has a decent number of businesses that run NTP for no good reason. All of this helps push it to the top spot. Russia finally shows up in second place, for similar reasons, though two of Russia’s major ISPs account for just over 40% of Russia’s exposure. China—with its vast IPv4 space and population—comes in at No. 3, which means businesses and ISPs have figured out needlessly exposing NTP can cause more problems than it’s worth.

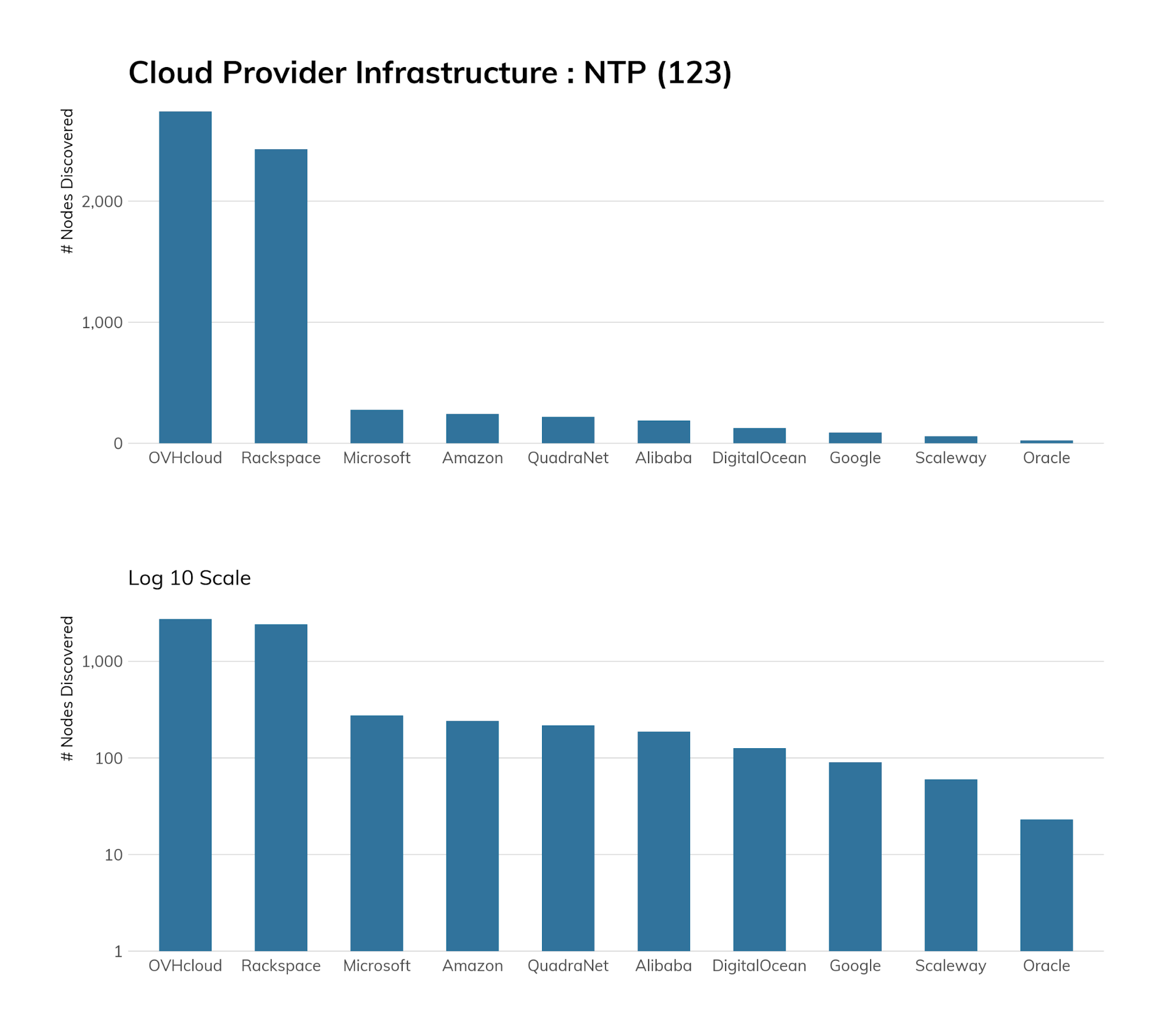

Rapid7 Labs was glad to see cloud environments (both the runners and the customers) seem to take the dangers of running NTP seriously as well, with most having almost no exposure.

Exposure information

Now, you know NTP has to be a bit dangerous if the main support site for the protocol itself has a big, bad warning about the dangers of NTP right at the top of its page. The biggest danger comes from using it for amplification DDoS (it is a UDP-based protocol). While it is still used today, there are way better services, such as memcached, to use for such things.

NTP servers are just bits of software that have vulnerabilities like all other software. When you put anything on the internet, bad folks are going to try to gain control over it. If an organization needs—for some odd reason—to run its own NTP server, there’s no reason it has to be on the public internet. And, if there is some weird reason it does, there’s no reason it has to be configured to respond to requests from all subnets.

Why are we picking nits? Well, it’s one more thing you’re not going to patch. Then, there’s the problem of all the information you might be giving to attackers about your network setup. In our NTP corpus, 255,602 (15.5%) reveal the private IP address scheme on the internal network interface.

| OS | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| UNIX (generic) | 1,089,876 | 69.61% |

| Cisco device | 294,330 | 18.80% |

| Linux+kernel version | 99,032 | 6.32% |

| BSD+kernel version | 38,798 | 2.48% |

| Juniper device+version | 32,469 | 2.07% |

| VMware+version | 8,597 | 0.55% |

| SunOS | 948 | 0.06% |

| Other | 657 | 0.04% |

| vxWorks | 505 | 0.03% |

| Sidewinder+version | 332 | 0.02% |

| QNX+version | 186 | 0.01% |

| macOS+version | 66 | 0.00% |

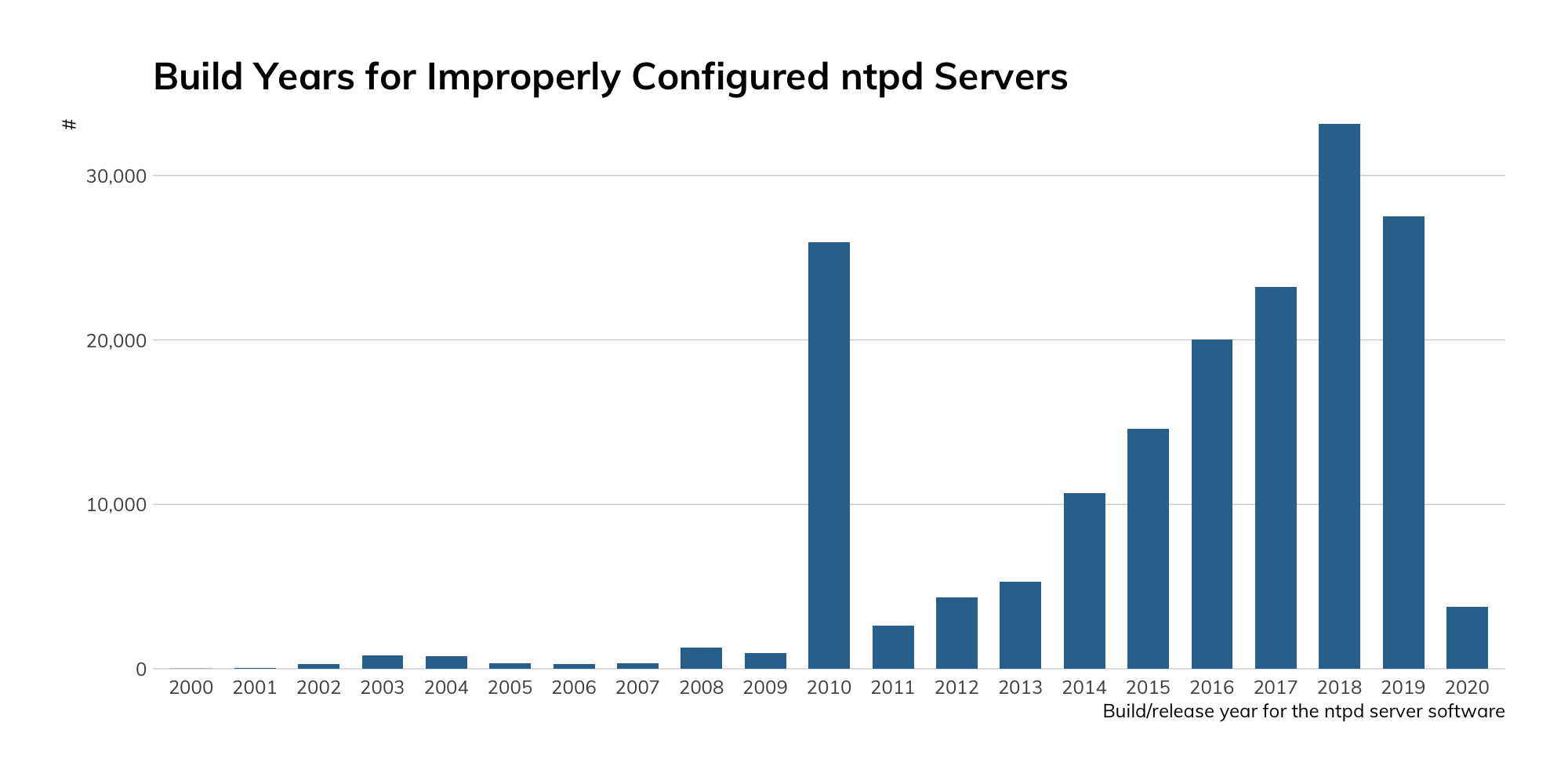

Over 1.5 million NTP servers give hints about the operating system and version they run. In total, 180,410 (11%) give us precise NTP version and build information, with all but roughly 4,000 giving us the precise release date:

There’s an [un]healthy mix of remote code execution, information leakage, local service DoS, and amplification DDoS spread throughout that mix of NTP devices.

Hopefully we’ve managed to at least start to convince you otherwise if you were thinking, “Well, it’s just an NTP server” at the start of this section.

Attacker’s view

The Exposure Information section provided a great deal of information on the potential (and measured) weaknesses in NTP systems. Attackers will judge your potential as a victim (and cyber-insurers will likely up your premiums) from how your attack surface is configured. NTP can reveal all the cracks in your configuration and patch management processes, and even provide a means of entry.

And, attackers still use NTP in amplification attacks, so that NTP server you didn’t realize you had or really thought you needed will likely be used in attacks on other sites.

Our advice

IT and IT security teams should use NTP behind the firewall and keep it patched. If you do need to run NTP externally, only let it talk to specific hosts/networks.

Cloud providers should keep up the great work by only exposing as much NTP as they need to and offering guidance to customers for how to run NTP securely (off the internet).

Government cybersecurity agencies should provide timely notifications when new vulnerabilities in NTP surface or there are known, active NTP DoS campaigns. Educational materials should be made available on dangers of exposing NTP to the internet and on how to securely configure various NTP services.