Executive Summary

As the world's knowledge workers were driven home amid a pandemic and cases of ransomware ran rampant across the internet, measuring the world's most critical businesses’ internet exposure is more important than ever. In this round of Industry Cyber-Exposure Reports (ICERs), researchers at Rapid7 evaluate five areas of cybersecurity that are both critical to secure to continue doing business on and across the internet, and are squarely in the power of CISOs, their IT security staffs, and their internal business partners to address.

These five facets of internet-facing cyber-exposure and risk include:

1. Authenticated email origination and handling (DMARC)

2. Encryption standards for public web applications (HTTPS and HSTS)

3. Version management for web servers and email servers (focusing on IIS, nginx, Apache, and Exchange)

4. Risky protocols unsuitable for the internet (RDP, SMB, and Telnet)

5. The proliferation of vulnerability disclosure programs (VDPs).

In addition to examining the internet-facing cyber-exposure of the Fortune 500, each section is accompanied by real-world, practical advice that practitioners can start implementing today. Note that this advice is not only for those CISOs who are privileged to hold positions in Fortune 500 companies, but also for those security experts who find themselves in business and regulatory relationships with members of this august collection of corporations.

Through the first half of 2021, Rapid7 will be releasing reports measuring these five critical areas of cybersecurity fundamentals across five of the most advanced economies of the world:

1. The United States Fortune 500 (this report)

2. The United Kingdom's FTSE 350 (the combined FTSE 100 and FTSE 250)

3. Australia's ASX 200

4. Germany's Deutsche Börse Prime Standard 320

5. Japan's Nikkei 225

Key Takeaways

The paper is divided into five detailed sections covering the areas mentioned above, and the overall takeaways of this research are as follows:

- The Fortune 500 is improving, though slowly and unevenly. At the end of 2020, email security significantly improved among the Fortune 500 as valid Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting & Conformance (DMARC) configurations grew from 314 to 379 from the end of 2019 (an increase of 13%). Vulnerability disclosure programs (VDPs) similarly gained popularity, especially among the top 100 companies (46% of which have some type of VDP).

- Fundamental cybersecurity exposure issues still trouble the Fortune 500. Unfortunately, outdated and vulnerable versions of popular web and email server applications—as well as nakedly dangerous protocol exposures of Windows Remote Desktop (RDP) and file-sharing (SMB), and Telnet—continue to plague IT administrators across the surveyed companies. We also looked at secure HTTP (HTTPS) and HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS) deployment, and found that while HTTPS is in use across the board, HSTS, a key web application security standard that ensures HTTPS is actually used, has only found purchase in the primary domains of about half of the Fortune 500.

Outdated and vulnerable versions of popular web and email server applications continue to plague IT administrators.

- The American healthcare system continues to be especially vulnerable to cyberattack. In a time when healthcare availability is more crucial than ever, the top of the healthcare business sector is especially worrisome. Only about half of healthcare-sector companies have implemented any DMARC controls to properly authenticate email communications. If vulnerabilities are discovered, only 17.5% of the sector appear capable of quickly receiving and acting on those reports. This deficiency in reporting capabilities may be a contributing factor to the outdated versions of Apache and Nginx web servers found running in healthcare IPv4 space, as well as the preponderance of discovered RDP endpoints exposed to the internet.

With these key findings in mind, the remainder of this report explores each of the five areas of cybersecurity measurable in the Fortune 500.

Before you dive in, we wanted to note that we performed this research before two major cybersecurity-related events unfolded: "SolarWinds" (December 2020) and "China Dropper/Microsoft Exchange" (March 2021). If your organization was and/or still is impacted by those events, you may be feeling like you are spending most of your time and energy dealing with emergencies rather than being able to focus on some of the more chronic issues outlined in this report. Since our goal is to help organizations become (and remain) safe and resilient, we have an appendix dedicated just for you that you may want to jump to first before tackling the sections below.

Email Security Among the Fortune 500

We all know and love—or at least begrudgingly rely upon—email. It is a pillar of modern communications, but is unfortunately also highly susceptible to being leveraged as a mechanism for malicious actions, such as spoofing or phishing.

A core concern regarding email is the authenticity of the source, and in recent years, DMARC has arisen as the preeminent email validation system. DMARC builds upon the foundations of two older email authentication systems, Sender Policy Framework (SPF) and DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM), which respectively check for mail server authorization (“Is the sender authorized?”) and email integrity based on key signatures (“Was the content altered?”). The various components of DMARC can serve to mitigate direct threats as well as potential reputational damage, such as spoofed emails intended to mislead partners, suppliers, or customers.

A properly implemented DMARC system can identify illegitimate emails and define how those emails should be handled. DMARC can be configured to handle emails of suspect provenance with different degrees of severity, depending on the aggressiveness of IT administrators. The DMARC policy options include:

None, where suspect emails are reported to a designated email address that serves to monitor DMARC notifications.Quarantine, where suspect emails are punted to the spam folder and a report of its receipt is delivered to the monitoring email address.Reject, where in addition to notifying the monitoring email address, suspect emails are not delivered at all.

By virtue of its efficacy in mitigating malicious messaging via email, we consider DMARC a significant risk mitigator and highly recommend its implementation. Unfortunately, while the benefits of DMARC are profound, its implementation is not global.

Unfortunately, while the benefits of DMARC are profound, its implementation is not global.

DMARC's implementations are tracked in public Domain Name System (DNS) records. To determine whether an organization utilizes DMARC only requires the examination of the organization’s published DMARC record. We are able to discern the scale and types of DMARC implementations by comparing the primary, well-known domains of the Fortune 500 organizations against their corresponding DMARC records that appear alongside DNS.

These published DMARC records are intended to be highly accessible. They are the means through which email recipients determine how to validate emails using DMARC, what email address to notify when receiving emails that fail DMARC validation, and what DMARC policy to apply in handling invalid emails.

Results

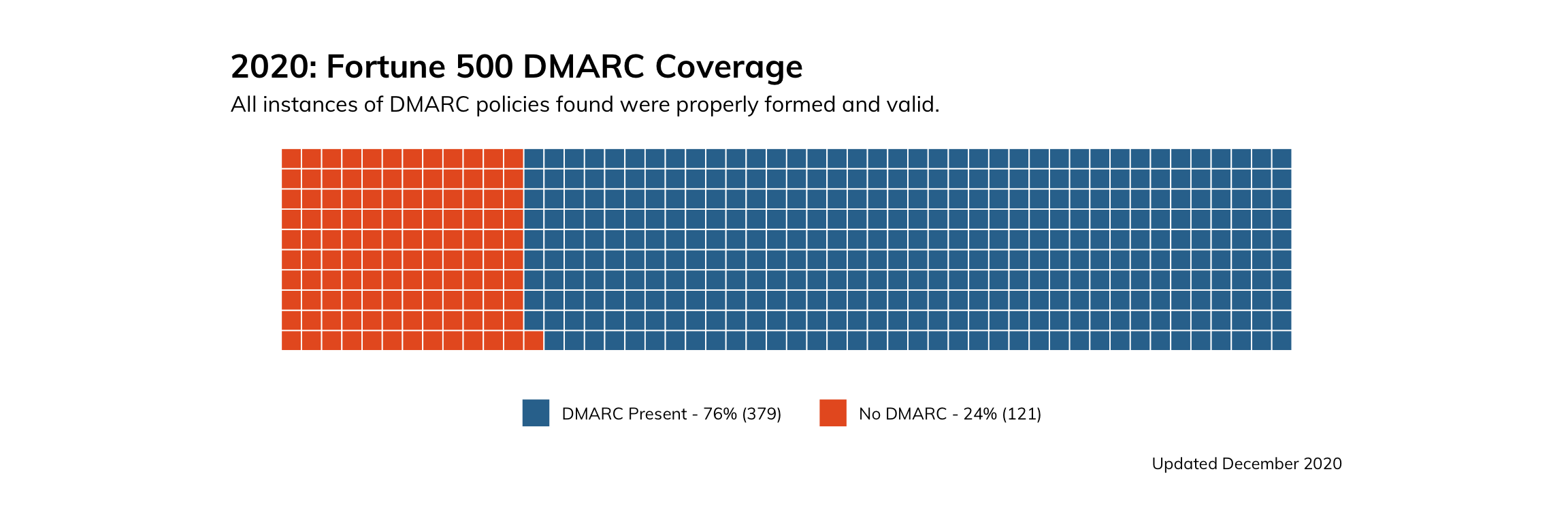

How is the Fortune 500 doing with regard to DMARC implementation? Not too shabby. While the coverage is not complete, we found that 379 (or approximately 76%) of the Fortune 500 had implementations of DMARC, all of which were valid.

Figure 1

By Industry

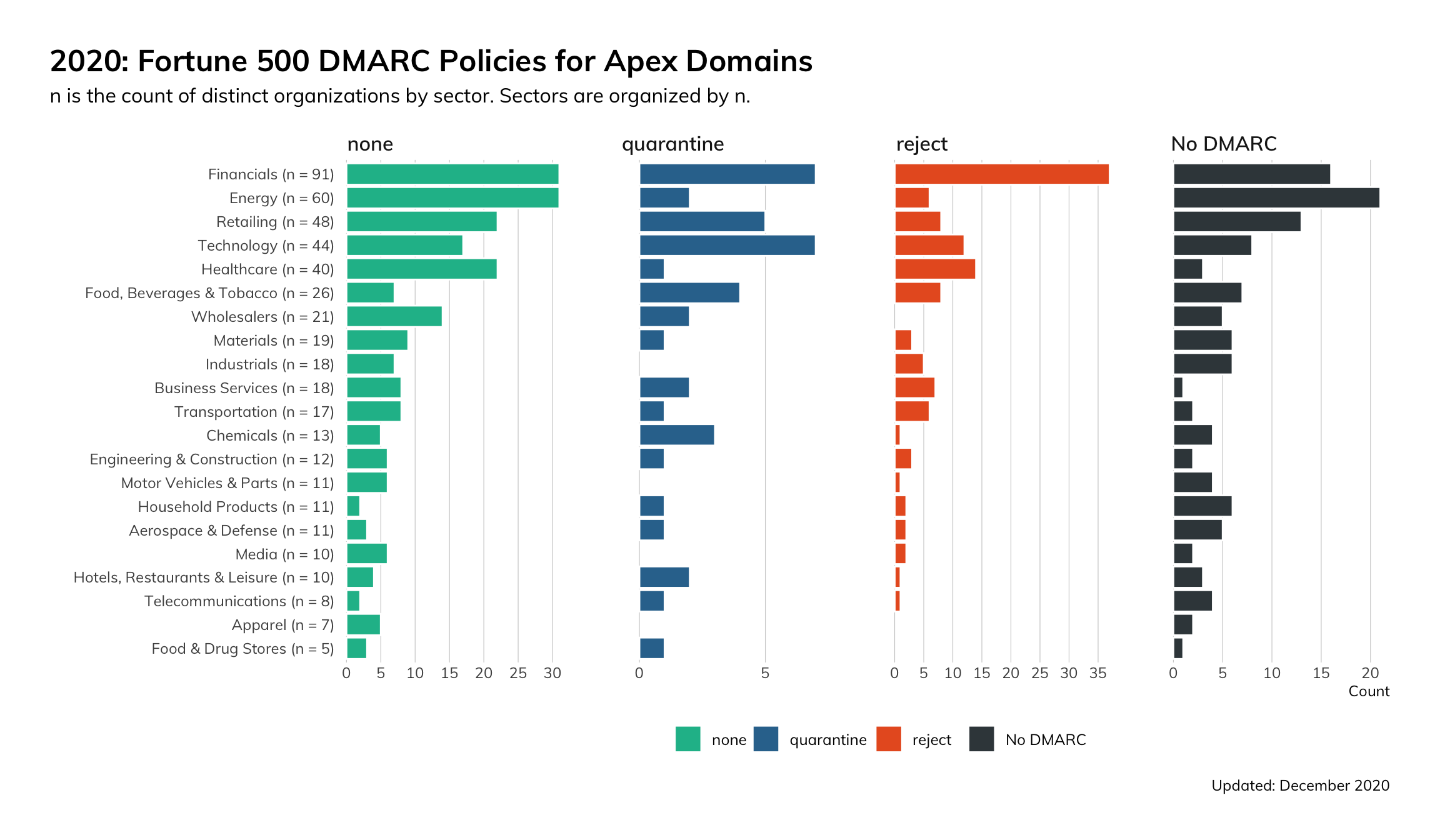

We find that in absolute terms, there are clear variations in terms of DMARC saturation for the different industries represented in the Fortune 500. When we examine the financials industry, for example, we find that many organizations are quite aggressive with their DMARC implementation with a reject policy in place, with a nearly equal number of organizations configured to simply monitor. The high degree to which DMARC is present for the financials sector is unsurprising, given that financial organizations were some of the earliest adopters of DMARC.

Somewhat disheartening is the lack of any DMARC implementations across all other industries to some extent. For opportunistic attackers who might leverage email as a means of exploitation, no industry is categorically off-limits.

For opportunistic attackers who might leverage email as a means of exploitation, no industry is categorically off-limits.

Figure 2

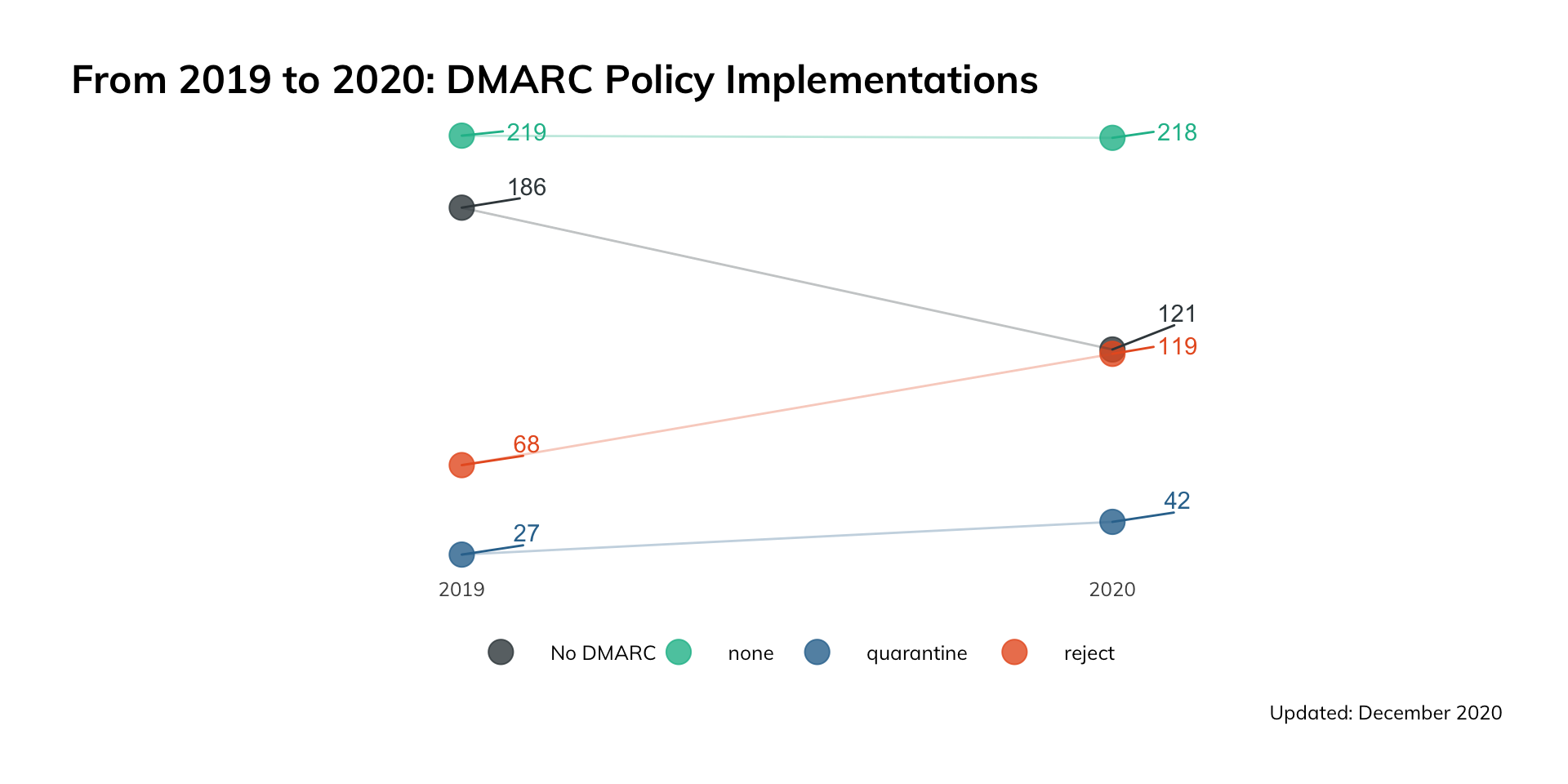

It is worth noting that while the state of DMARC across the Fortune 500 is not perfect, there has been respectable progress. From 2019 to 2020, the number of organizations within the Fortune 500 that had no valid DMARC implementations declined from 186 down to 121—a difference of 65 organizations. The increased adoption of DMARC in that period corresponded with an increase of 51 DMARC records set to reject (a 75% increase), as well as an increase of 15 records set to quarantine (a 55% increase).

The number of domains that persisted from year to year with a DMARC policy of none (i.e., report only, but take no action) remained fairly constant. This implies that there were a sizable number of organizations that adopted a set-it-and-forget-it attitude—they probably implemented a minimum standard of DMARC at some point because it was recommended, but have since either forgotten about it or have chosen not to improve on it, neither of which are ideal.

Nonetheless, in 2020, the Fortune 500 in aggregate became notably more hardened to illegitimate emails.

CISO Takeaways

If DMARC has not already been implemented in your organization, take proactive measures to get it set up.

Figure 3

Nowadays, DMARC can be thought of as a foundational fixture of email hygiene, and it broadly signals an organization’s commitment to modern information security norms. Furthermore, lacking a DMARC implementation leaves an organization potentially blind to malicious email campaigns that are not captured through some form of DMARC monitoring that can be informative in terms of scale, source, and severity.

Once the decision has been made to implement DMARC, it’s time to consider the policy implementation in a more nuanced manner. An aggressive reject policy is highly secure but might result in legitimate emails being blocked. A more forgiving quarantine policy could strike a balance between preventing aggravation and allowing for some form of recourse. At the very minimum, a DMARC implementation of some form should be in place to monitor for illegitimate or poorly configured email traffic.

Web Service Security Among the Fortune 500

The vast majority of the interactions an average person has with technology is through some form of a web application, but what constitutes a “web app” can be considered quite nebulous, and the security controls for hardening these applications are equally broad. APIs, distributed authentication schemes, single-page applications, and static websites all might fall under the general category of “web application.” There are very few security measures that should be applied to all web applications across the board without further subdividing what specific type of application we are referring to. However, there are a couple that we will examine here.

All web applications should require strong encryption, with a vanishingly small number of exceptions. While this is most critical for applications that are serving up critical or sensitive information, such as personally identifiable information (PII), it is important even if you serve only static informational content. There is a common misconception that the risk of using an insecure connection is a loss of confidentiality—that the information a user is browsing could be observed by a malicious third party. While this certainly is a risk, it is often overlooked that a lack of encryption makes the connection vulnerable to modification (a loss of integrity). This means that malicious third parties could not only observe potentially confidential information, but that they could alter that information or inject their own content that could potentially compromise your users.

The risk of malicious content injection exists regardless of whether your web application serves sensitive information or just cute pictures of cats. Due to this universal risk to a site’s users and to the overarching brand reputation of the site owner, we will consider the support of strong encryption (in our case, TLS) and the enforcement of its usage via HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS). For the purposes of this section, we will look at the primary domain for each company, as it is the domain that is most responsible for a company’s brand reputation.

The risk of malicious content injection exists regardless of whether your web application serves sensitive information or just cute pictures of cats.

HTTPS Support

HTTPS is the protocol that ensures web traffic is encrypted and secure. There are a few ways that HTTPS could be configured in an environment.

- Not available (HTTP only)

- Available and optional

- Required (HTTP "Strict Transport Security", or HSTS, configured)

- Required with HSTS preloading

Supporting HTTPS for your site is table stakes for having a web presence at all, with requiring encryption following very closely behind. HSTS preloading does carry some technological challenges, but they are challenges that a web security program should be working to proactively address.

With all this said, let's share some good news right off the bat: Among the sites we examined in the Fortune 500, 100% of them supported HTTPS.

HSTS Adoption

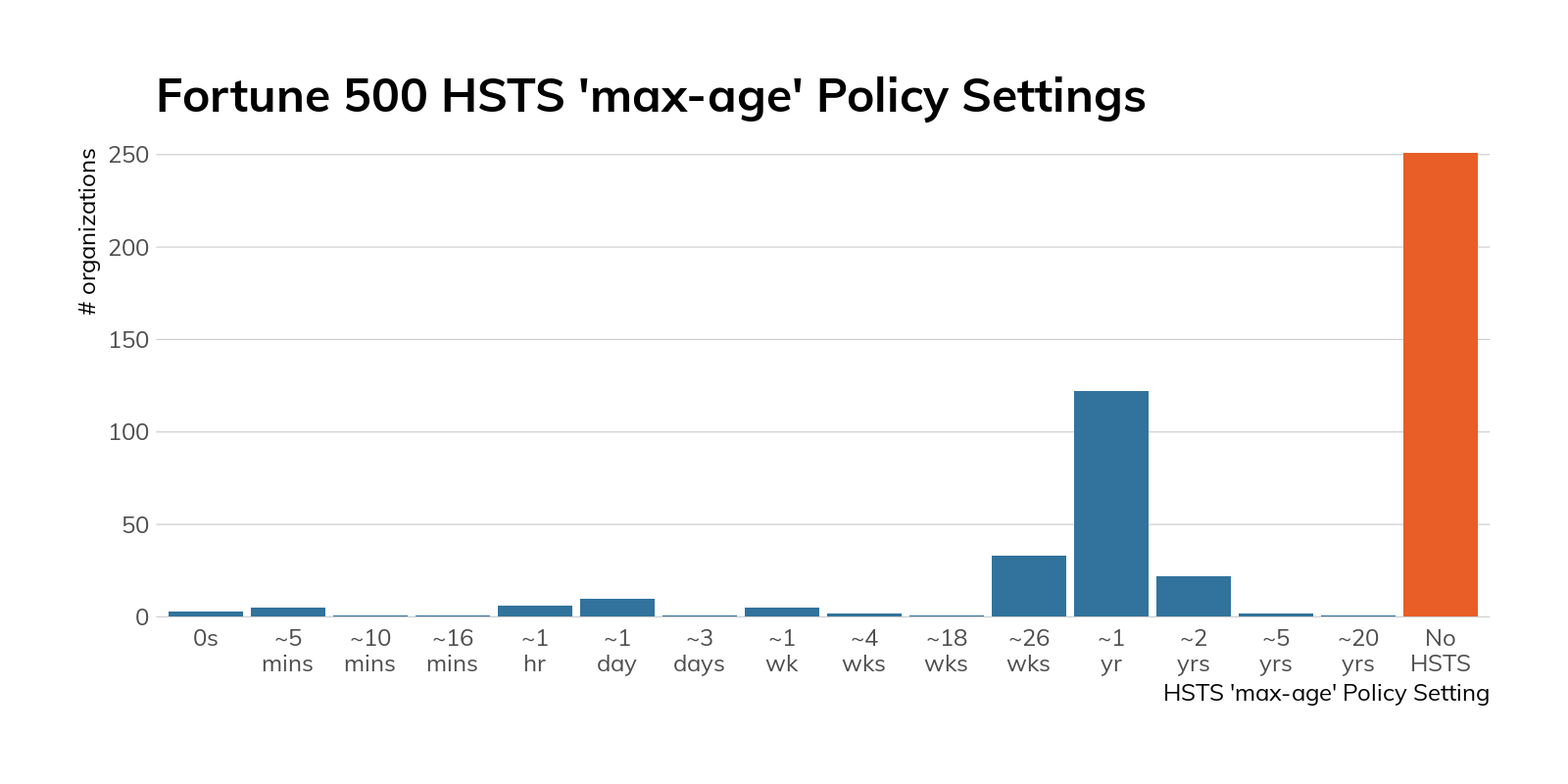

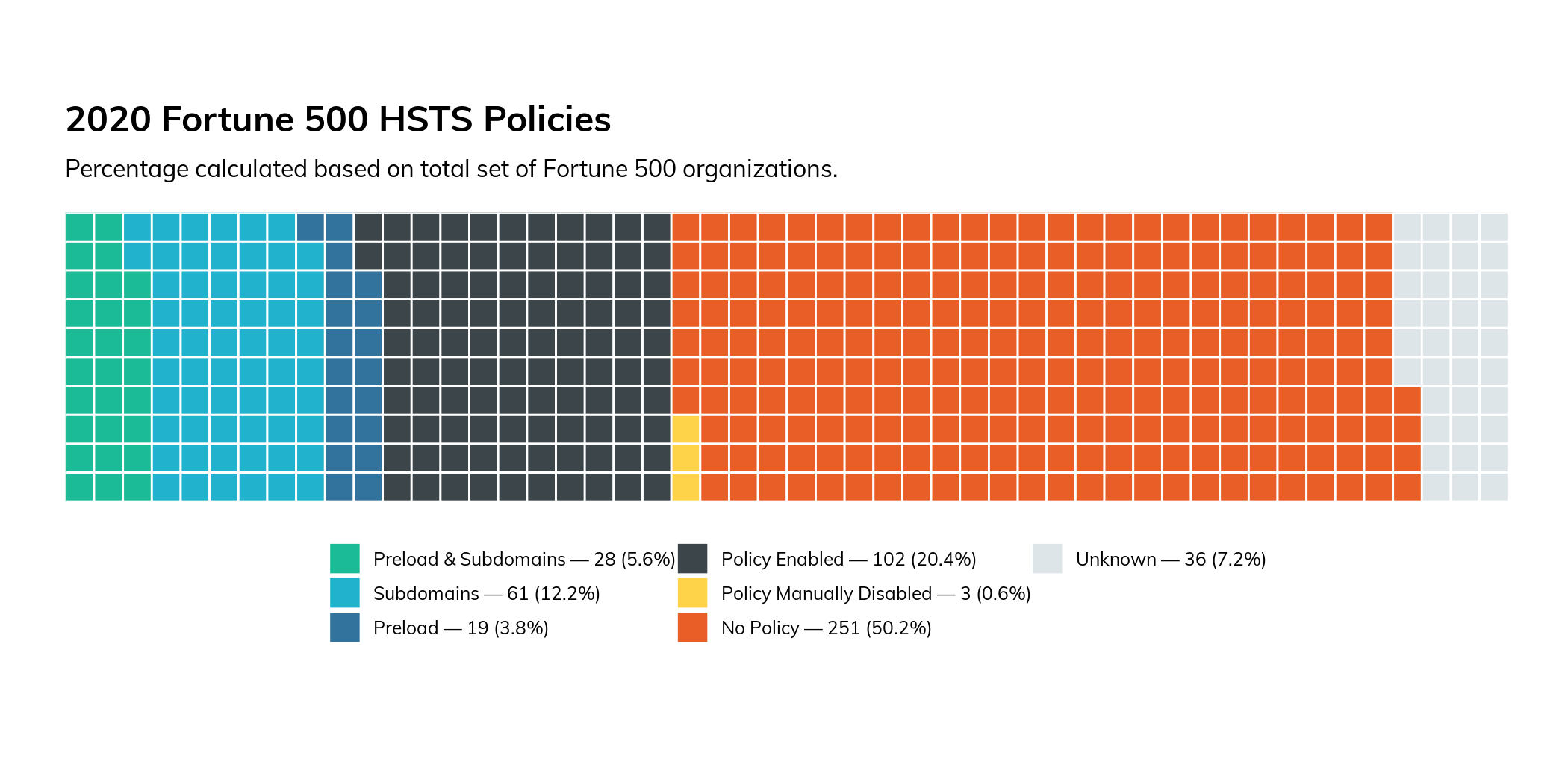

The outlook for HSTS adoption was not quite as impressive.

Figure 4

As you can see, just under half of the sites examined supported HSTS in some capacity. While this may seem decent at a cursory glance, if the site already fully supports HTTPS (and these sites all do), it should be relatively trivial to implement HSTS to guarantee your users visit the secure version of your site. Many of these sites do provide a redirect from the insecure version of their homepage—however, that will not mitigate a man-in-the-middle (MiTM) attack.

Figure 5

Of the sites that do support HSTS, three of those sites have actually configured it to be explicitly disabled (as of the study time of January 2021), meaning they had supported HSTS at one time, but no longer do. Hopefully this was a temporary measure to resolve an implementation issue.

Eighty-nine percent of sites that support HSTS also support the “includeSubDomains” directive, protecting the entire domain and all subdomains. This is a fantastic security feature that can be difficult to implement in certain situations.

Forty-seven of these sites support the “preload” directive. This directive will cause crawlers to automatically add your site to a global list of known sites that support HSTS. If a supporting browser is directed to a site with HSTS enabled, it will guarantee that the first connection is always conducted over HTTPS, meaning it eliminates the one, single place where your site’s users are vulnerable to MiTM attacks—the first connection to your site before an HSTS header has ever been encountered. This configuration option is a simple way to add an extra layer of protection for your users, and if you bother to enable HSTS, you should certainly add this option. While it’s a somewhat newer directive with less browser support, there is no downside to including it (browsers that do not support HSTS will simply ignore it).

Summary

Securing and encrypting traffic to your user-facing domains is not only good practice, but it also protects your corporate brand. Securing HTTP with TLS has been a major point of focus for the web security community for the past several years, and for good reason. All of the Fortune 500 companies fortunately provided a secure version of their primary website, but they have a long way to go before they come up to snuff in terms of best practices. The lack of proliferation of HSTS across the F500 is a good indicator that their application security programs are falling behind, especially since other, more sophisticated, mitigations can be significantly more complicated to implement. While the standards certainly move quickly, it’s important to keep up to speed, especially when your brand reputation is on the line.

Securing and encrypting traffic to your user-facing domains is not only good practice, but it also protects your corporate brand.

CISO Takeaways

If you haven’t thought about your site’s encryption for a while, now might be the time to revisit it. A company’s brand reputation is on the line when consumer-facing web applications suffer from security failures, and it’s important to consider this fact when making investment decisions in various security programs. If your company’s website is not supporting HSTS, it might be worthwhile to find out why. Is it a technical, organizational, or budgetary constraint? Finding the cause could be a great springboard for re-evaluating your entire application security program.

Version Complexity Among the Fortune 500

As noted in the introduction, we performed our Exchange research before the release (and, ensuing chaos) of the out-of-band Microsoft Exchange patch in early March 2021. What you see in this section has changed rather dramatically since then, and we'll be posting some follow-up Exchange research on the Rapid7 blog after this report is released.

Complexity is the enemy when it comes to successful security outcomes in an organization. Diversity in systems, technologies, and business processes present real, daily challenges for even the most mature security teams, especially when it comes to patch and vulnerability management. Patching even one major vulnerability can be a Herculean task in many places. Diversity compounds complexity within each technology component. That is to say, an organization may have multiple different web server technologies in use. Each technology, in turn, may have its own hodgepodge of versions, which directly (negatively) impacts configuration management and patch management.

Complexity is the enemy when it comes to successful security outcomes in an organization.

To get a feel for how well these well-resourced organizations are performing in this area, we looked at three separate factors:

- The diversity of the portfolio of a selected technology—web servers—in use by each organization.

- How well maintained this portfolio is.

- How well organizations maintain critical services, such as email gateways.

Our findings show that:

- Within a single technology stack (web servers), organizations in a staggering number of industries—Business Services, Financials, Healthcare, Leisure, Industrials, Media, and Technology—expose 10 or more different versions of Apache and/or Nginx. All industries have one or more members exposing three or more different versions of IIS. This increases their respective attack surfaces and makes it difficult to deploy patches (when they bother to apply patches) due to testing and quality assurance complexity.

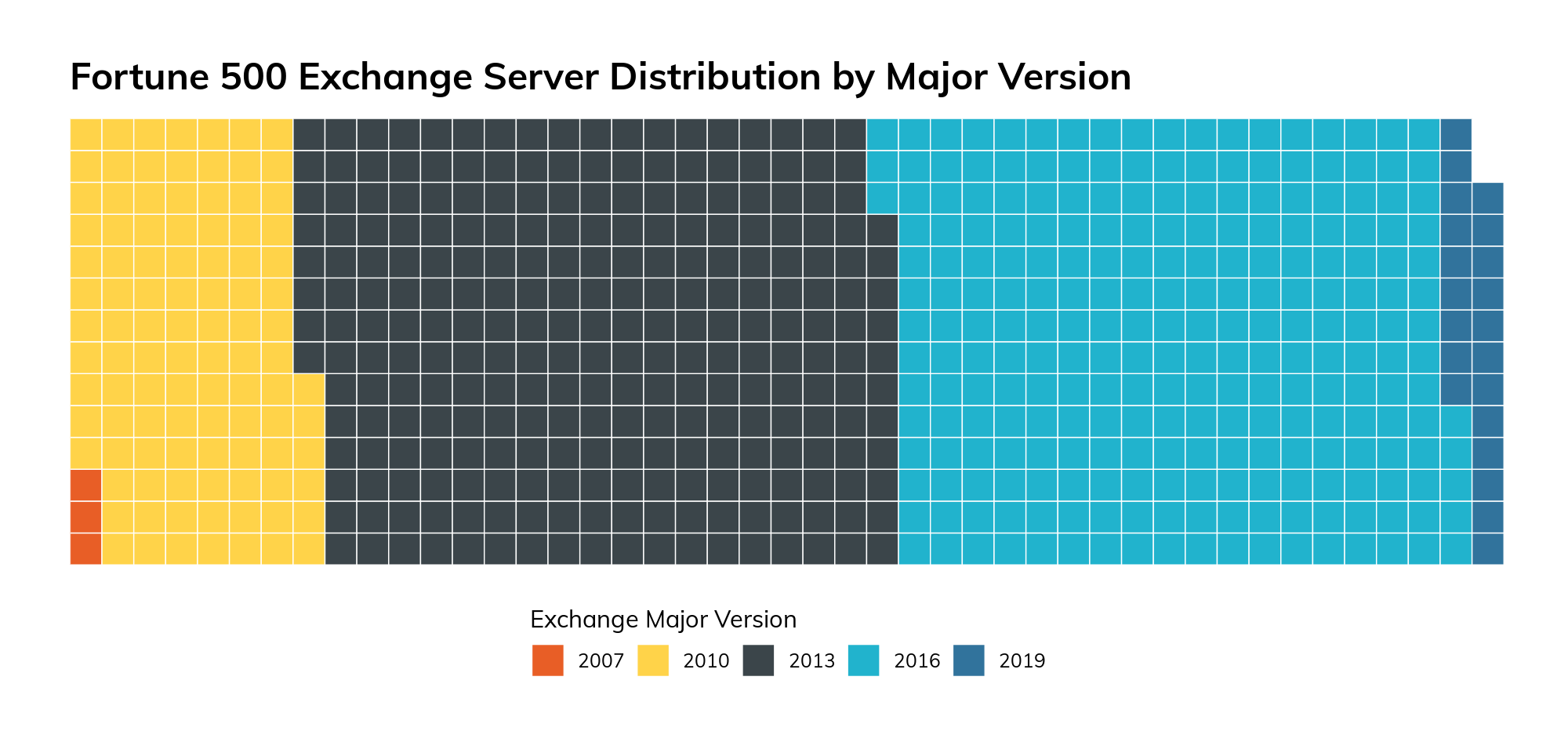

- Organizations have serious difficulty keeping critical IT infrastructure—such as Microsoft Exchange—current. Only around 19% (30 out of 160) of Fortune 500 that still run self-hosted Microsoft Exchange are running current/supported versions. Further, 18% are running end-of-life versions of Exchange 2007 and 2010, putting them at risk of future vulnerability exploitation.

We used Project Sonar1 and Recog2 to identify internet-facing technologies—e.g., web servers, file servers, DNS, SSH, etc.—that were in use for each organization in the Fortune 500. We then mapped them to available Common Platform Enumeration3 (CPE) strings. This methodology has some limitations in that the results are constrained by:

- The fingerprints available to Recog

- How promiscuous each fingerprint service is (i.e., whether Recog can extract version information)

- The ports and protocols Project Sonar studies

- Our measurement of only IPv4-space

- Sonar honoring IPv4 opt-out requests

These constraints, if anything, generally result in underreporting of the magnitude of the findings.

Version Dispersion Among Web Servers

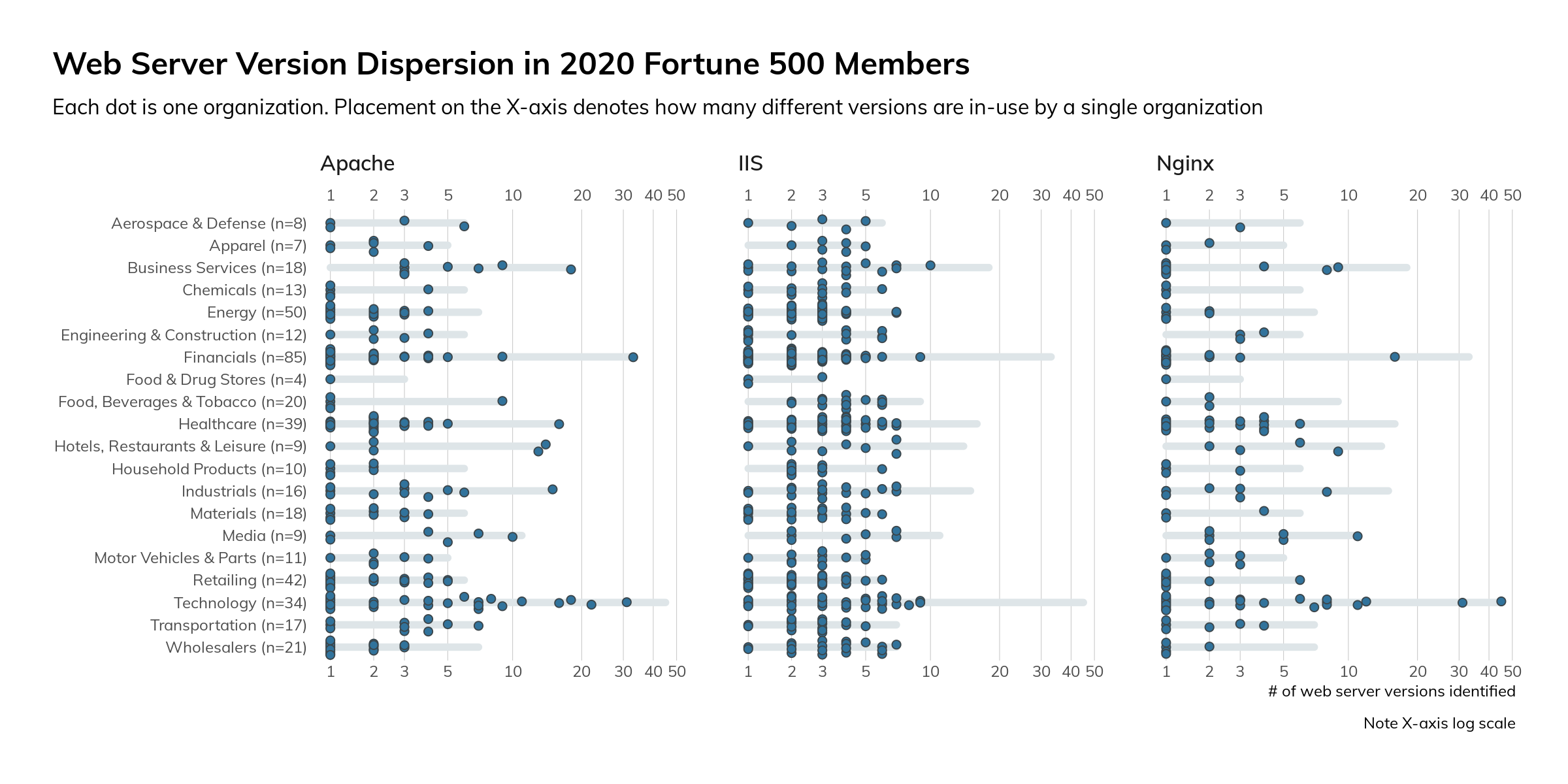

Back in 2018, when we began our first foray into analyzing the cyber-exposure of the Fortune 500, we created the term “version dispersion” to refer to the diversity of versions within a service component an individual organization was exposing to the internet. With the dramatic rise4 in enterprise use of tooling such as Kubernetes,5 we expected to see a reduction in version dispersion of the three web servers—IIS, Apache, and nginx—that we previously measured.

There are at least over 81 distinct versions of Nginx6, 70 distinct versions of Apache, and 15—yes, 15—distinct versions of IIS7 running across Fortune 500 members. Let’s see how that stacks up per industry.

There are at least over 81 distinct versions of Nginx, 70 distinct versions of Apache, and 15 distinct versions of IIS running across Fortune 500 members.

Figure 6

A higher density of points toward “1” on the X-axis means that each of the organizations those points represent are running with a low version dispersion. This means they have better control over server/service deployments and configurations, have fewer versions to test patches against, and can make changes faster and with more confidence than others. It also likely means they have a more rigorous “you must be this tall to deploy a server on the internet” rules than organizations that are further to the right on the X-axis. Attackers and cyber-insurance assessors alike notice such things and may be more likely to target organizations that exhibit a more “wild, wild west” stature.

Version Dispersion: Focus on Microsoft Exchange

Some internet-facing services are more important than others. It’s one thing to have a crusty old Apache HTTPD server attached to the internet, which may only have a denial-of-service weakness. It is quite another thing to run old versions of what most organizations would (or, should) deem critical infrastructure, such as Microsoft Exchange servers or VPN/gateway/remote access services.

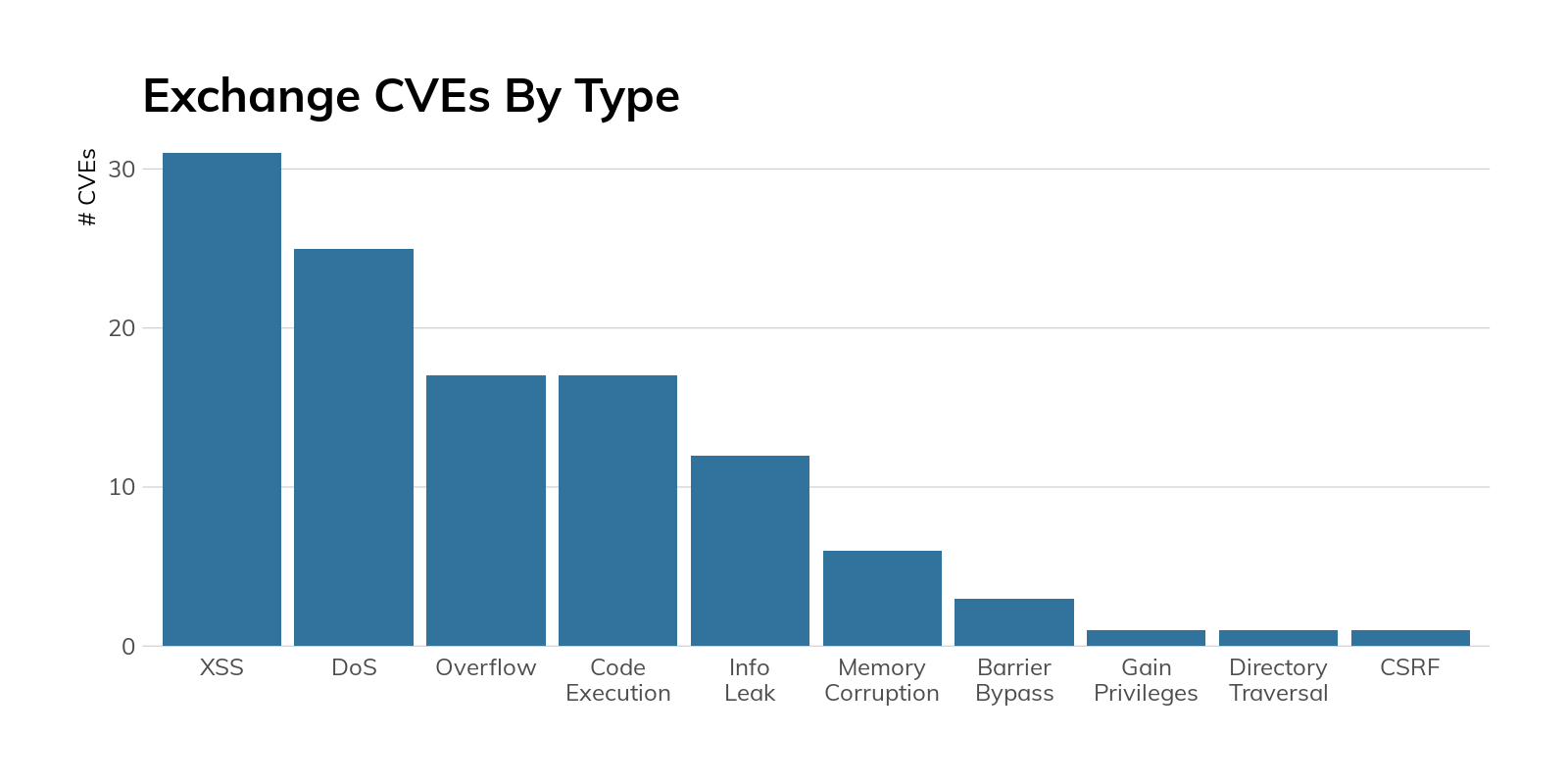

To get a feel for how well these organizations maintain critical services, we’ll take a peek at Microsoft Exchange hygiene, as nearly 40% of Fortune 500 organizations still8 have at least one internet-facing Exchange server handling business-critical email, and Exchange has had a fair number of weaknesses—of varying criticality—uncovered over the years:

Figure 7

Surely these organizations take care to ensure this vital service is at peak resiliency, at least when it comes to security patches. Right?

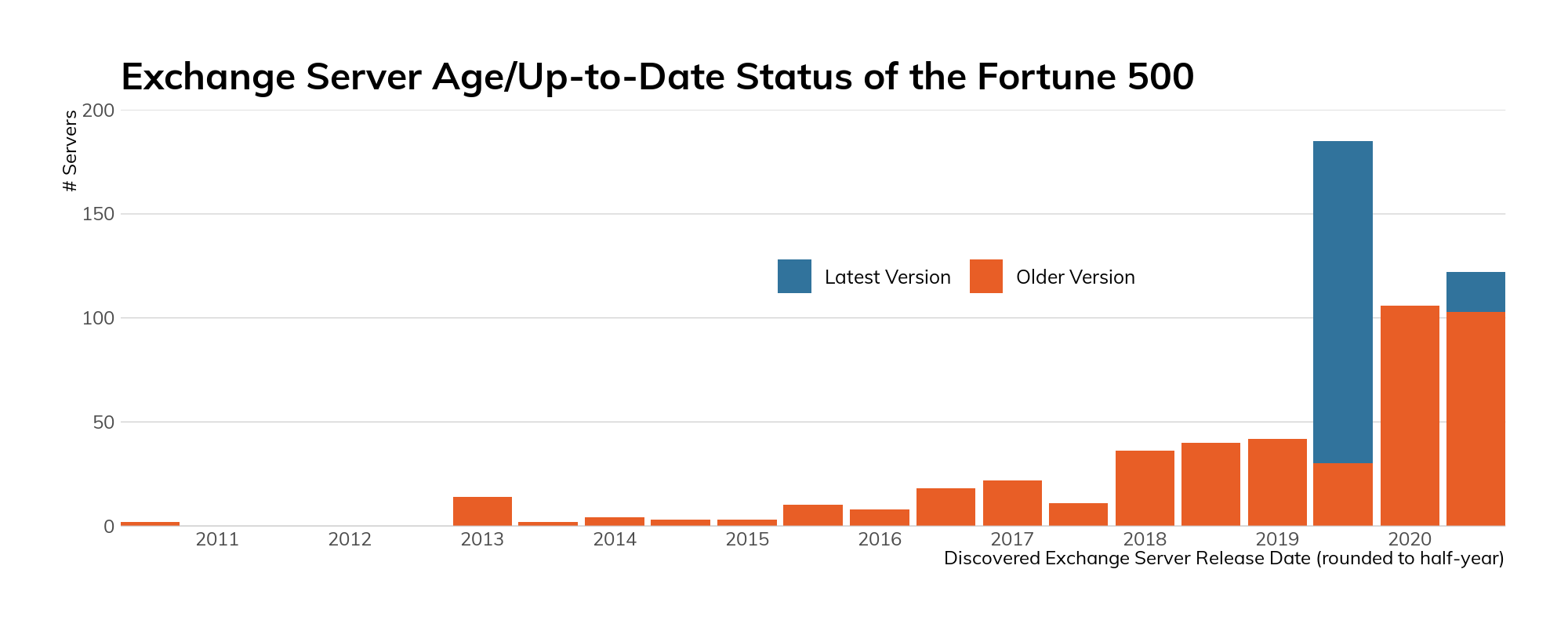

Figure 8

The above figure paints a fairly disturbing picture of the state of Microsoft Exchange in the Fortune 500 in both currency (i.e., age of some server versions) and whether the deployed version is supported9 by standard Microsoft support contracts.10 On the plus side, 31% of discovered, precise-version fingerprinted instances are 2020 releases, 72% of which are at a version normally supported by Microsoft.

Fortunately, only a few are running Exchange 2007 (which has been at end-of-life status for a while). Unfortunately, a sizeable chunk of the Fortune 500 did not seem to get the memo11 about Exchange 2010 reaching end-of-life status in October 2020.

A sizeable chunk of the Fortune 500 did not seem to get the memo about Exchange 2010 reaching end-of-life status in October 2020.

Figure 9

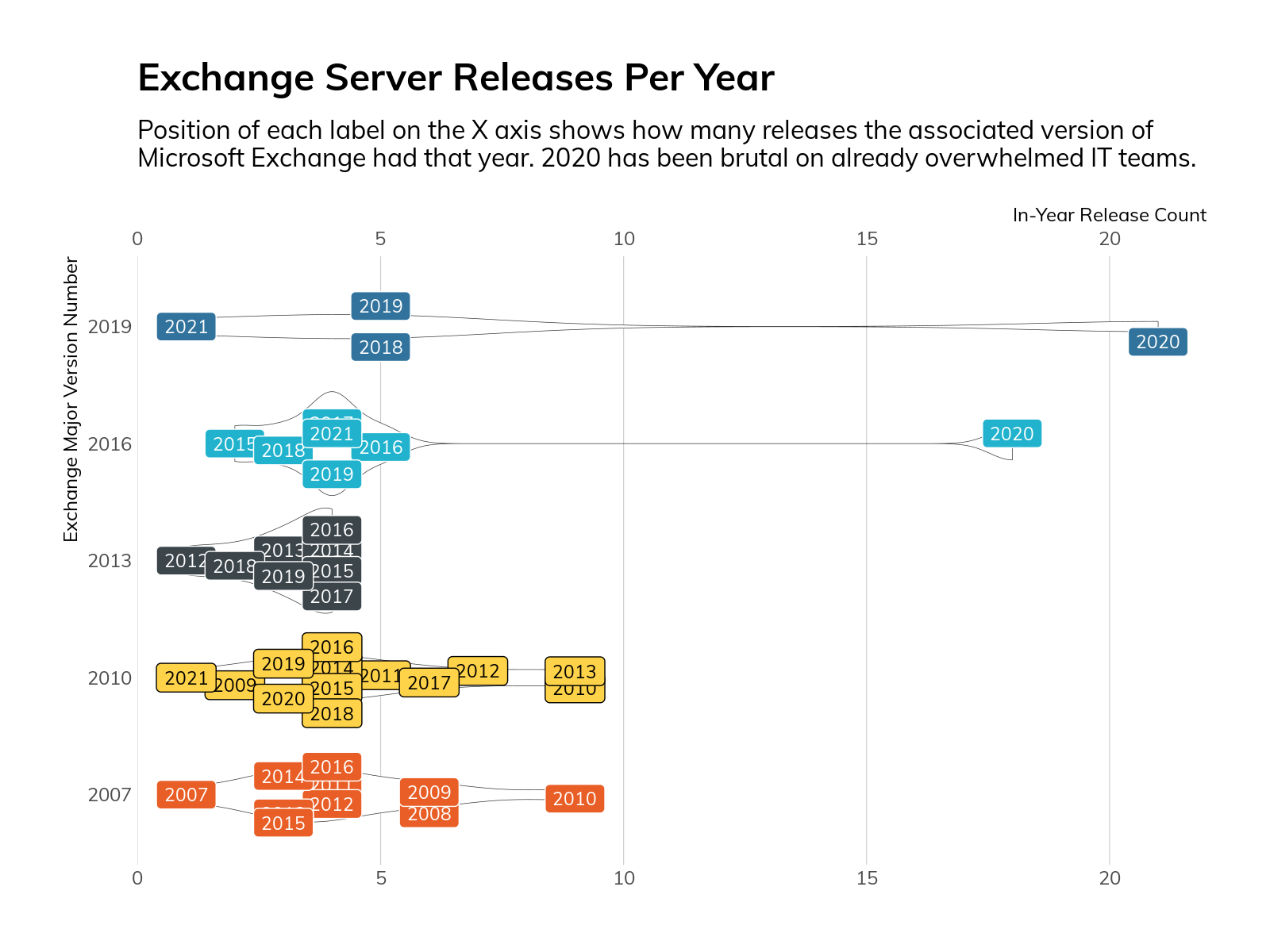

Oddly enough, organizations that run Exchange 2013 do a much better job of keeping current than those running more recent releases. This appears to be largely due to Exchange 2013 having far fewer in-year updates than its siblings.

Figure 10

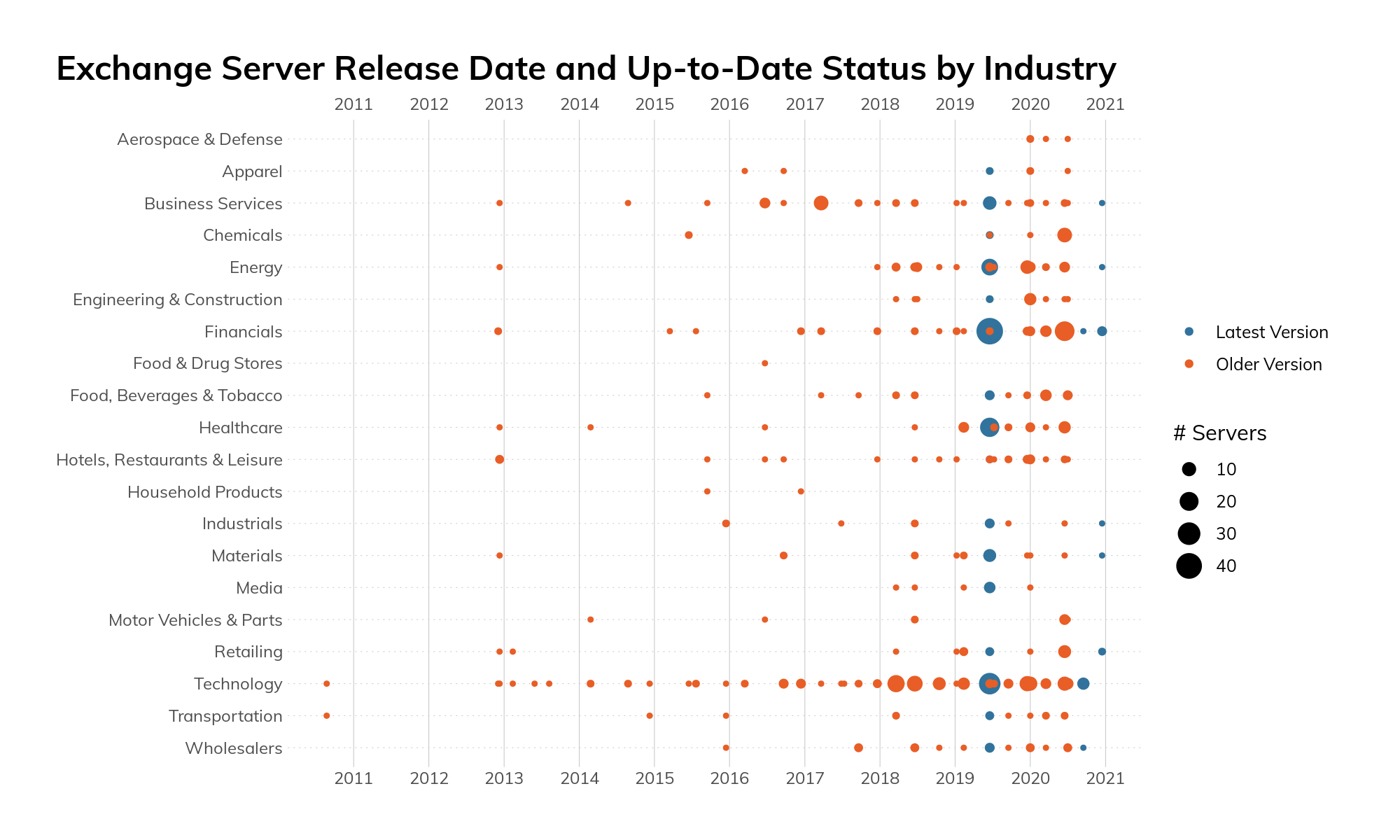

And, the outlook is still pretty grim across industries.12 Figure 11 shows release and support status of Exchange deployments in each industry, and virtually all of them are having trouble keeping current.

Figure 11

For those as curious as we were about that thin line of “supported” blue points right at the tail end of 2020, the build is “14.3.509”. This is a very recent—and unlisted on Microsoft’s support page—version of Exchange 2010, so it looks like it may not be so end-of-life after all.13

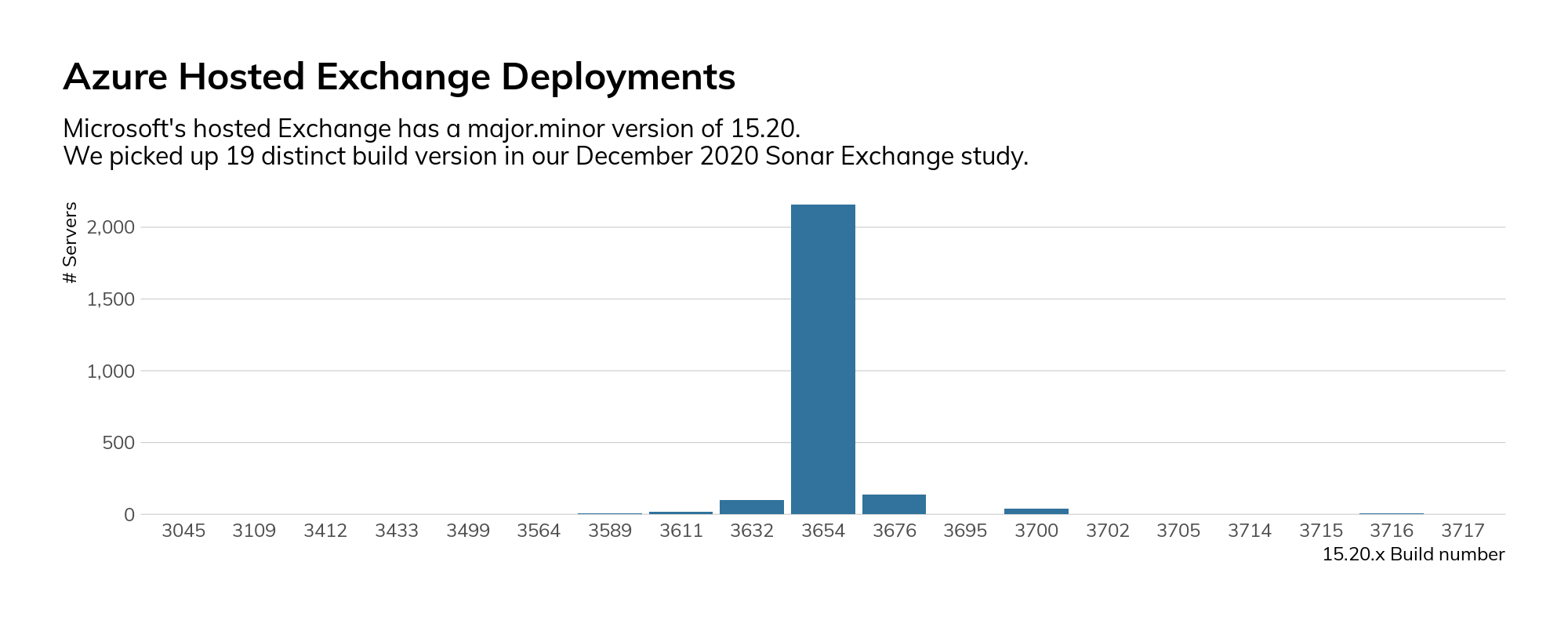

If keeping Exchange deployments updated, secure, and resilient is a challenge for you, take some comfort in the fact that even Microsoft has issues normalizing hosted Exchange (Microsoft 365) build levels.

Figure 12

CISO Takeaways

For this chapter, we’ll be talking to two different sets of CISOs: those who see their image reflected in the mirrors in each of the sections, and those who have organizations like this as business partners or suppliers.

If you’re a security leader who is working to build resilience and safety into the DNA of your organization, issues such as technology sprawl, version management, and critical service maintenance are non-negotiable must-haves. The good news is that these aren’t just “security” issues. Organizations deploy services to meet a business need, and it is far easier to sustain service uptime and stability if there are fewer moving parts to maintain. To achieve buy-in with your peers, collect historical and current data regarding service degradation (and/or outages). Add to that data how long it takes IT, application, and operations teams to support each component of each business process. If you pair that up with information on the volume and severity of identified weaknesses (CVE-based or otherwise), you will find areas that have a solid business case to warrant partnering for improvement. As each area ameliorates, you’ll have far more agency to affect change in other, lagging areas.

For those who shuddered at what this section revealed, make sure these are areas you look for when evaluating third parties on behalf of business process stakeholders in your organization. It’s fairly straightforward to both ensure you’re asking about these potential areas of weakness and verifying14 that the answers you receive are accurate. There’s no guarantee that the internal exposure of organizations reflects what is seen externally. However, it is generally more likely that the internal picture is even worse than what is presented to the outside world. Holding your partners and suppliers to a higher level of safety and resilience will not only lessen the risk to your organization, but can also have a cascading positive effect as other organizations follow the standards you’re setting.

High-Risk Services Among the Fortune 500

There are certain services that are generally considered to be high-risk when found available on the public internet. As an example, with very few exceptions, 15 placing SMB file shares on the internet is considered a Bad Thing. Doing so may expose data, leak environmental information such as domain names, enable brute force attacks against credentials, and provide a vector for exploiting vulnerabilities in the Windows Server Message Block (SMB) implementation, as was seen in the Conficker16 and WannaCry17 worms.

In our research across the public internet, we know that we’re only seeing a surface level of information, and we often try to find ways to understand what it is telling us about the organizations that operate these services. We can look at configuration and protocol details and use them as proxy markers for the internal environment and security maturity of an organization.

For example, if we discover an SMB service and can detect that it doesn’t support SMBv2, 18 which was introduced in Windows Vista 19 and Server 2008, we can make certain assumptions about the age of the operating system and/or requirements for legacy compatibility.

If an organization permits Telnet 20 connections to routers from a different country, we can make assumptions about the age of the equipment as well as the security policies for secure protocols and network access control lists (ACLs).

In order to get a sense of how well the Fortune 500 organizations were performing in this area, we surveyed SMB, Windows Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP), and Telnet on the default ports in their public IPv4 address space and reviewed service data where present.

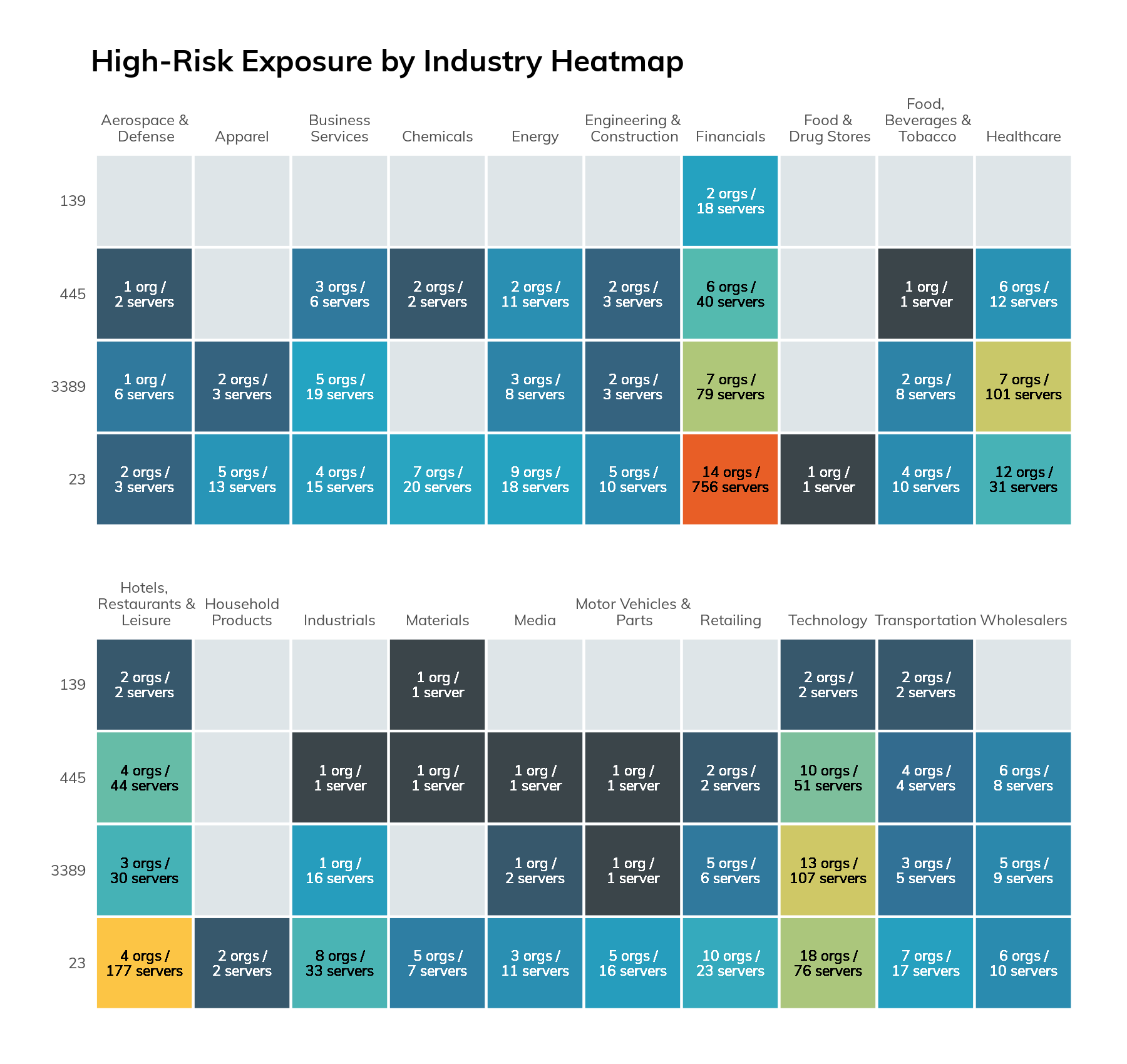

Our findings show that:

- Most of the exposure was in two industrial groupings: Financials and Hotels, Restaurant, and Leisure.

- Of those hosts exposing SMB, 95% provided a hostname, 91% leaked the DNS name of the host, and 92% leaked the fully qualified domain name (FQDN) configured on the host.

- RDP 403 services were found across 61 companies. These were heavily skewed toward the Technology, Healthcare, and Financials industries.

- The Financials industry dominated the Telnet exposure list with 61% of the total.

We used Project Sonar and Recog to identify internet-facing SMB, Windows Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP), 21 and Telnet services on the default ports that were in use for each organization in the Fortune 500. In each case, we fully negotiated the protocol to verify that we were indeed communicating with the expected service. This methodology has some limitations in that the results are constrained by the fact that:

- Services are only observed on the default ports. Telnet and, less commonly, RDP can be moved to non-default ports.

- Measurements are made only in IPv4-space.

- Certain IP ranges are not examined by Sonar by request.

- Certain cloud and ISP related ranges were excluded.

These constraints, if anything, generally result in underreporting of the findings.

Findings: RDP, SMB, and Telnet

We should start this section by stating that any non-zero number of these services made available to the general internet is considered to be unacceptable in organizations with mature security programs. Followers of the Rapid7 blog and past Rapid7 research reports will be quite familiar with this advice, but looking at the calendar here in 2021, we have to note that it's been a while since the last major worm outbreak on the internet. NotPetya (SMB) was 2018, WannaCry (also SMB) was 2017, and Mirai (Telnet) was way back in 2016. Despite all the vulnerability and exploit churn we saw in 2019 and 2020, we appear to be overdue for another self-replicating issue across open ports to insecure services. Closing off your exposure to these services will certainly save you weeks of cleanup later.

Windows Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP)

While some may think that RDP should be considered an exception to this rule, we'd argue that there are commonly available techniques and technologies such virtual private networks (VPNs), RDP gateways, and firewall access control lists (ACLs) that remove the risk related to this technology and so, as a general rule, RDP shouldn’t be exposed to source addresses outside of the organization.

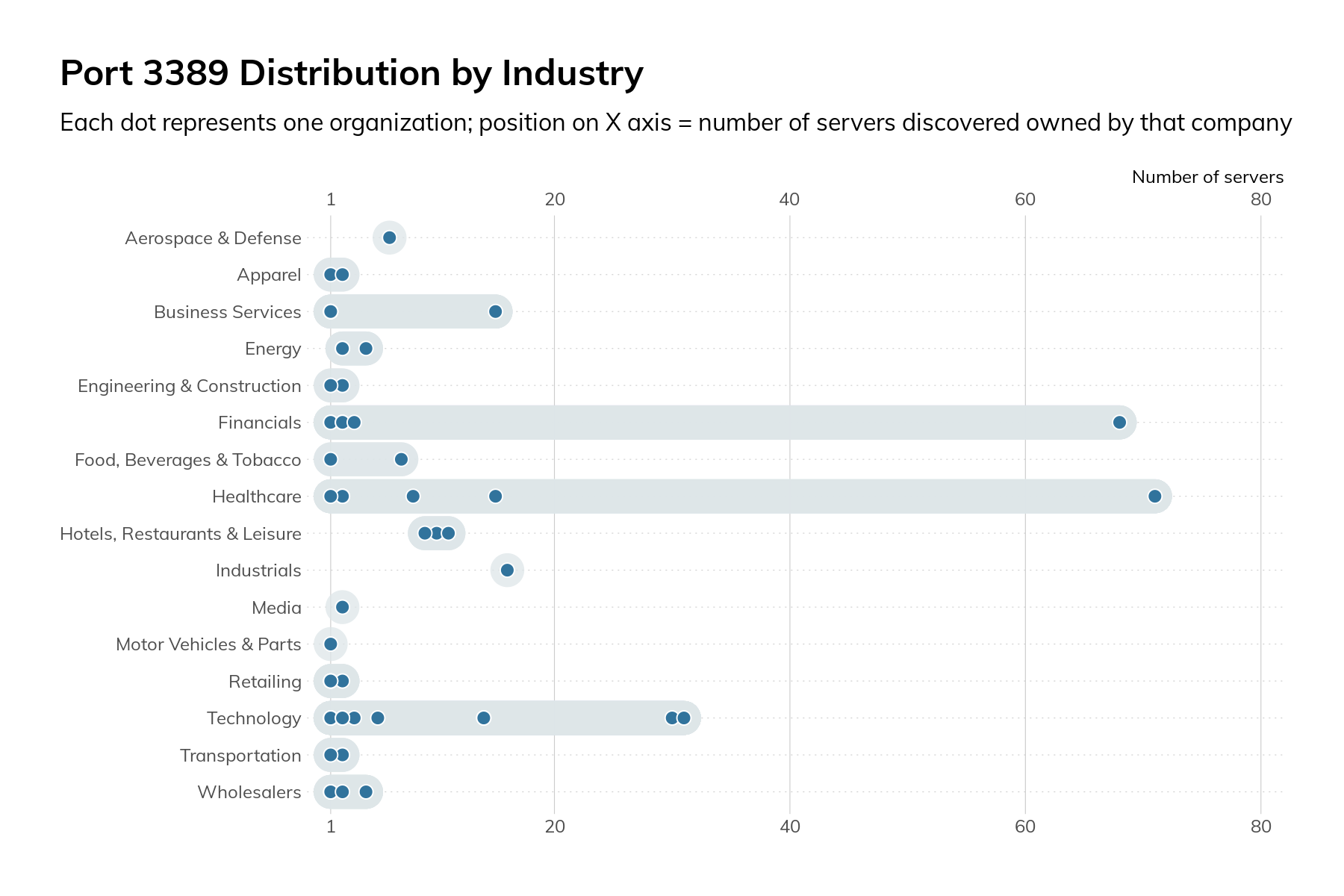

Since we’re on the topic of RDP, let's start with the discussion with the findings there. On the default RDP port of 3389/tcp, we observed 403 services across 61 companies. These were heavily skewed toward the Technology, Healthcare, and Financials industries.

Figure 13

The graphic above shows that the overall numbers are mostly attributable to just a few companies and aren’t inherent to the operations of a specific industry.

On a positive note, when we looked at the security requirements for RDP authentication, we found that 92% required Network-Level Authentication (NLA). 22 NLA, introduced in Windows Server 2008, enforces Transport Layer Security (TLS) protection of traffic in-flight, strengthens authentication options, and significantly reduces the risk and impacts related to brute force and certain denial-of-service attacks. NLA has been enabled by default since Windows 2012. The lack of NLA serves as a proxy indicator for older infrastructure either on the server itself or a requirement for compatibility with older clients. The only other reason for not having NLA enabled is that it doesn’t allow authentication with expired passwords. That is another reason to deploy RDP gateways, VPNs, or other infrastructure to provide facilities for changing the password as well as enable security access to remote desktop services.

On a positive note, when we looked at the security requirements for RDP authentication, we found that 92% required Network-Level Authentication (NLA).

Windows Server Message Block (SMB)

The SMB protocol is for file- and print-sharing as well as interprocess communication on Windows and compatible networks. We say this in every report, 23 but SMB should never be exposed to the internet. The risks include data leakage from file shares, credential compromise via brute force attacks, and malware infection (think of the previously noted Conficker and WannaCry) via vulnerabilities in the host operating system or service. Given the plethora of options for securely sharing files, SMB shares aren’t worth the risk.

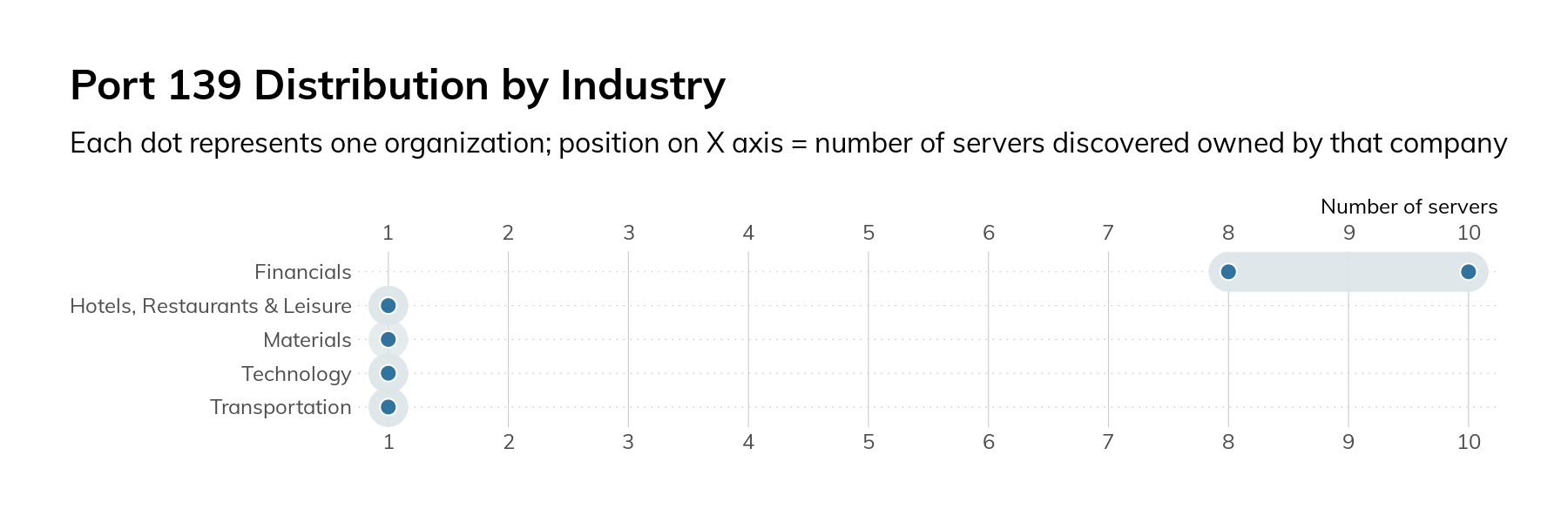

When we surveyed the Fortune 500, we decided to look at two different SMB ports: 139/tcp and 445/tcp. Port 139/tcp is used for older variants of SMB, and its presence is generally a sign of very old software and legacy requirements. In our surveys, we only found 25 servers across nine companies. Most of these are running an open source SMB server called Samba. 24 The oldest version of Samba we observed was released in late 2007 and contains quite a few critical vulnerabilities.

Figure 14

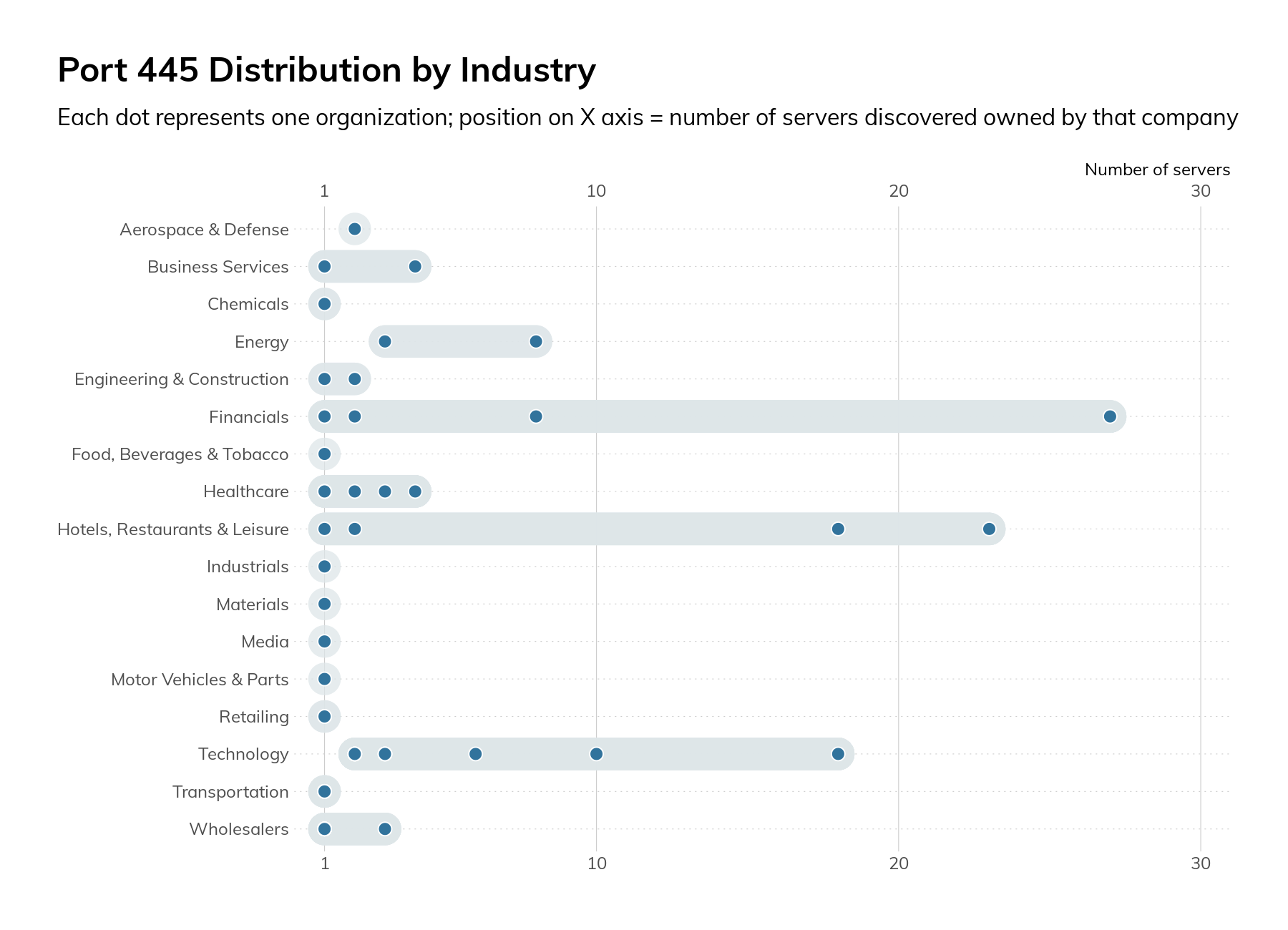

We also surveyed SMB on port 445/tcp. Introduced in Windows 2000, this transport for SMB removed some of the legacy protocol overhead. In our research, we observed 190 servers across 53 organizations. As in the case of RDP, most of the servers were attributed to just a handful of companies.

Figure 15

The mere presence of these SMB servers on the internet is cause for concern, but when we dug into the protocol configurations, the concern increased. All 190 servers supported SMBv1, which means they are missing several critical security controls, and attackers can force clients to downgrade to SMBv1 from more secure versions of the protocol. Also, 11% only supported SMBv1 and none of the more modern versions. We strongly recommend Microsoft’s guidance on SMB v1. 25

SMBv3.0 was released with Windows Server 2012 and included many security and performance improvements, 26 such as encryption of data on the wire and protocol downgrade protections. Only 60% of the observed servers supported any version of SMBv3.

Only 60% of the observed servers supported any version of SMBv3.

These SMB services also leaked information about the organization. Of the 190 services, 95% provided a hostname, 91% leaked the DNS name of the host, and 92% leaked the fully qualified domain name (FQDN) configured on the host. This information may indicate role (VCENTER01) or indicate internal organizational structure (db1.prod.us.corp.local).

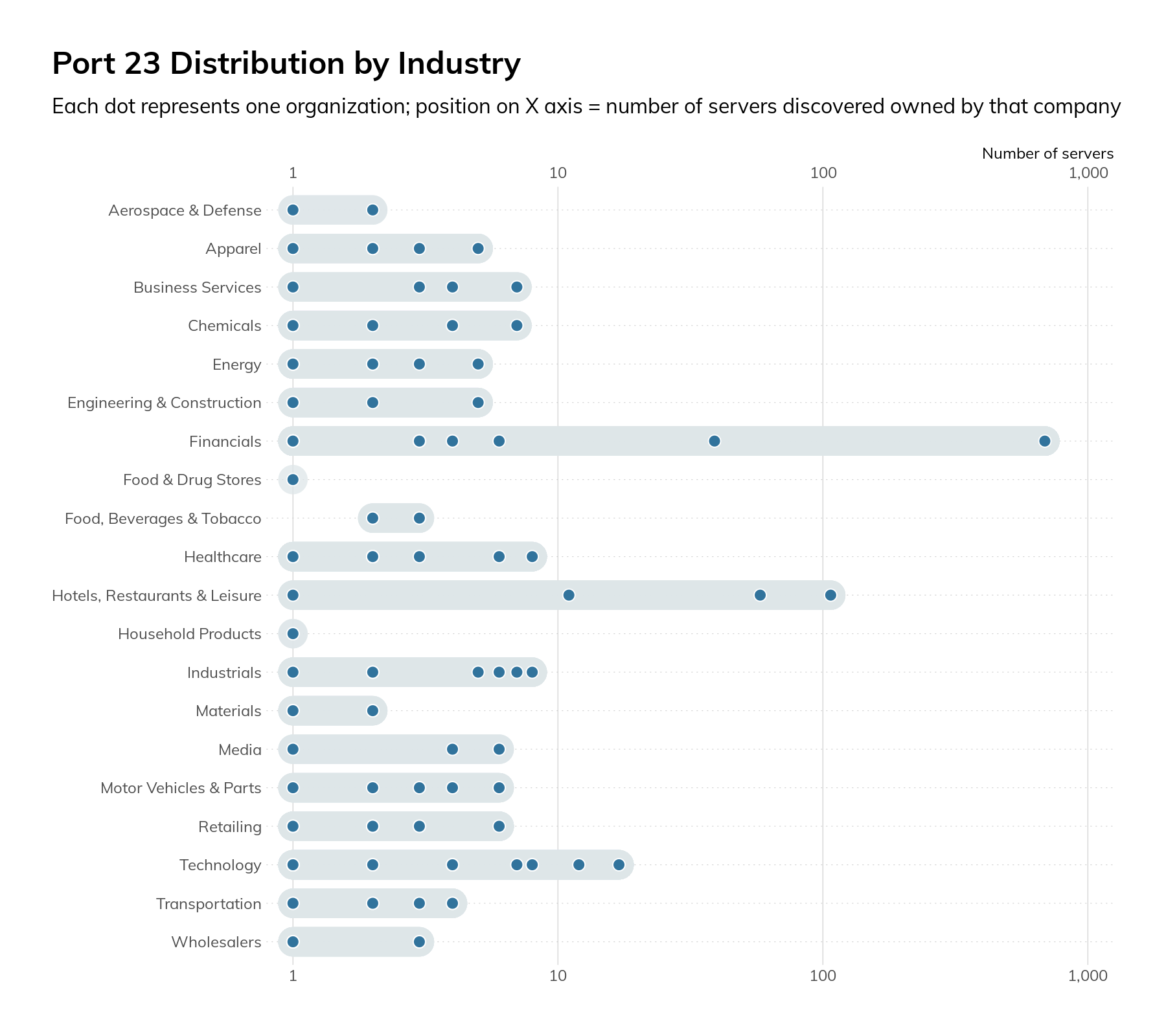

Telnet

Telnet is a plaintext-based protocol used for providing remote console access to devices. It nearly always transmits credentials and data in cleartext and has no protections against man-in-the-middle (MiTM) injection of commands or data. Originally specified in 1969, Telnet is well past its “Use By” date and has been superseded by other more secure technologies such as SSH. Our survey found 1,249 hosts across 131 companies. The vast majority of these hosts (756) were in the Financials industry, followed by 177 in the Hotels, Restaurants, and Leisure industry grouping.

Figure 16

Most of the equipment was found to be a router or switch, though there were a handful of printers, industrial control systems (ICS) gateways, cameras, firewalls, and servers. As a general rule, it’s considered insecure to use Telnet as opposed to more secure protocols such as SSH. Also, if Telnet is unavoidable, firewall access control lists (ACLs) and other controls should be used to limit which internet IPs can access the devices. Since our survey process had to make connections from multiple IPs—in some cases in different countries—to validate a service, we can say that this was likely not in place or overly broad.

When we look across the surveyed protocols and industries, we can see that there are certain hotpots.

Figure 17

While we would expect to see more exposure in the Technology industry, the highest level of exposure was actually observed in two industries: Financials and Hotels, Restaurant, and Leisure. This is due to the outsized impact of just a few companies, which we will not name for obvious reasons. One company was responsible for 44% of all IP addresses that exposed at least one risky service. The next highest was a company that controls 8% of the list. On a more positive note, when excluding cloud and ISP network ranges, we did not observe these services on the default ports for 337 of the Fortune 500 companies.

One company was responsible for 44% of all IP addresses that exposed at least one risky service.

CISO Takeaways

The findings here indicate that even some of the most resourced companies are exposing services that have an outsized risk.

Our guidance for addressing the risks above isn’t to implement some advanced security controls or software, but to instead return to the basics. You can find all of them in the early parts of the CIS Top 20 27 controls.

- Develop and maintain an inventory of internet-facing hosts that includes software versions, roles, and services that are expected to be exposed, as well as the reason why. Make sure that this inventory is validated by outside-in scans of all of your public-facing IP ranges.

- Implement security policies and supporting configuration standards that enforce the use of secure protocols and configuration settings. Using the example of Telnet, every device currently using Telnet should be able to support SSH—and if it doesn’t, it is too old or insecure to be directly connected to the internet.

- Ensure that software and hardware are kept current. In many cases, such as with Microsoft Windows, newer software brings better security features and controls. Older software’s lack of these features can force security trade-offs and require the implementation of compensating controls, which add complexity.

Vulnerability Disclosure Programs Among the Fortune 500

Every major corporation on Earth is a technology company. 28 It is unthinkable that a business that generates billions of dollars in revenue and employs thousands of workers would not have a significant technological investment in their products, processes, and logistics. We rely on fantastically advanced technology in every aspect of our modern lives. Of course, anyone who has spent any time analyzing these technologies will notice that we are routinely bedevilled with vulnerabilities, especially when it comes to internet-based technologies.

As it happens, we have a powerful and proven method to stem the tide of vulnerabilities in major technologies: coordinated vulnerability disclosure 29 (CVD), and a now-standard mechanism to participate in CVD, vulnerability disclosure programs 30 (VDPs).

The presence of a publicly-accessible VDP is conspicuously lacking across most of the companies in the Fortune 500, which, in turn, makes it difficult for those companies to ever learn about vulnerabilities in their products and technical infrastructure in a constructive way.

The presence of a publicly-accessible VDP is conspicuously lacking across most of the companies in the Fortune 500.

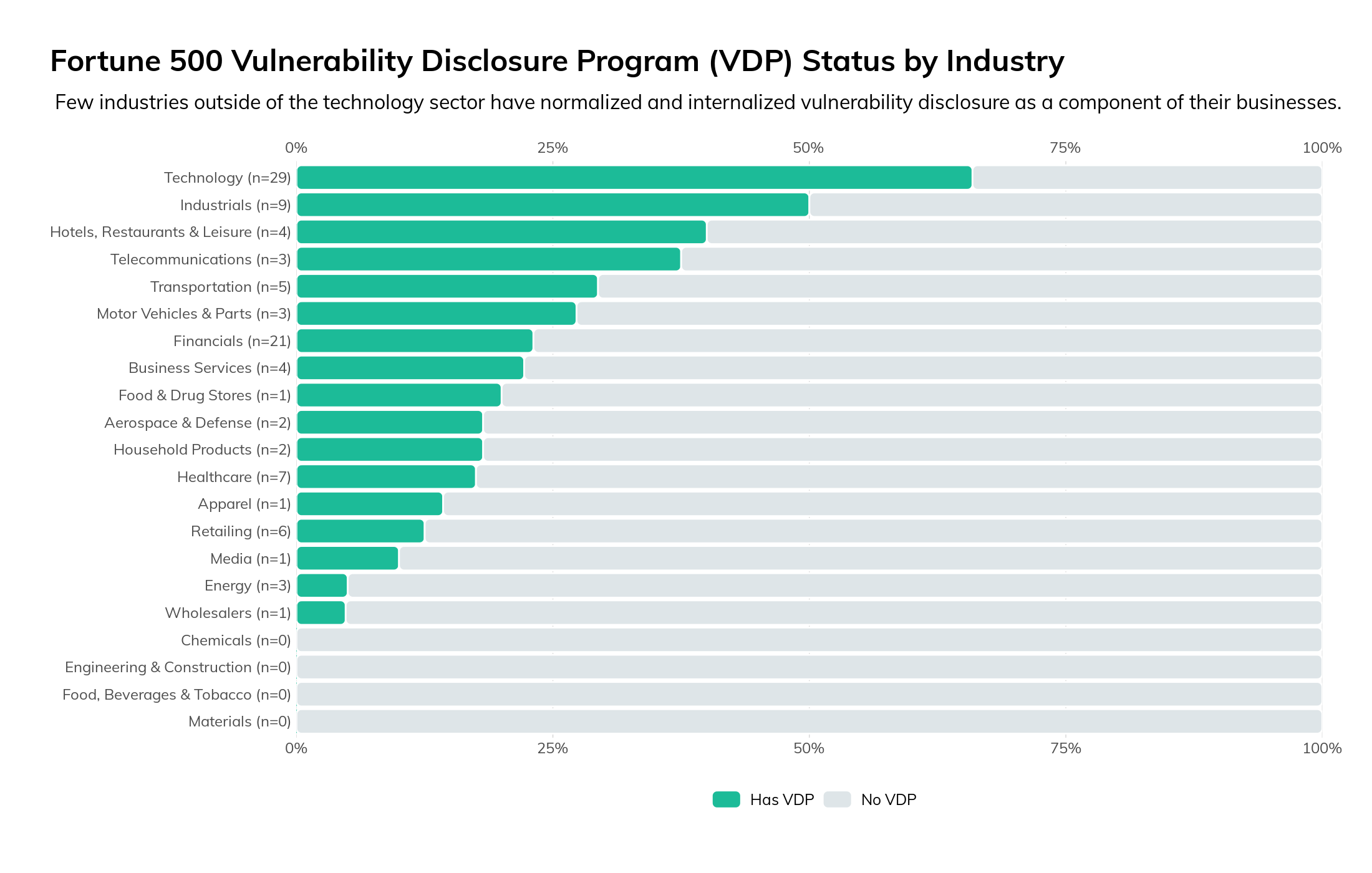

While VDPs are more common today among the highest-revenue companies, the drop-off is rather steep after the top 100 companies, and few of the 21 industries represented in the Fortune 500 have normalized VDPs as a business practice. Without vulnerability disclosure programs, these industries are telegraphing that they do not want to know about their own vulnerabilities, intentionally or not, to their shareholders' and customers' peril.

For this study, we searched for VDPs associated with Fortune 500 companies and flagship brands of those companies, much in the same way we would if we were about to disclose a vulnerability about those companies' products or services. Specifically, we looked for the following, in this order:

- The presence of a VDP associated with all Fortune 500 companies (or flagship brands of those companies) listed on either Bugcrowd’s 31 or HackerOne’s 32 crowdsourced bug bounty lists, or in the Disclose.io 33 program database.

- The presence of a standardized security.txt file on each company or flagship brand website to facilitate the sharing of discovered vulnerabilities with website maintainers.

- An obvious pointer to, or indication of, a VDP offered by the candidate companies by Googling the terms "vulnerability," "disclosure," and "security" along with the company name and flagship brand.

The initial survey was conducted in December 2020 and reviewed again in January 2021.

It is possible some of the surveyed companies that appear to not offer a VDP do, in fact, have a process for receiving vulnerability intelligence, but the lack of an easily discoverable VDP drastically undercuts the effectiveness of the VDP for both researchers and the companies.

Assessing the relative merits of individual VDPs is beyond the scope of this paper, but it should be noted that not all VDPs are created equal—some offer robust "safe harbor" protections for researchers and accidental discoverers when reporting and publishing vulnerabilities, while others seek to bind researchers in restrictive agreements about what can be assessed and how results are to be handled and communicated. For this paper, the mere existence of a VDP, no matter how liberal or restrictive, counts as a positive.

Results: Prevalence of VDP Adoption

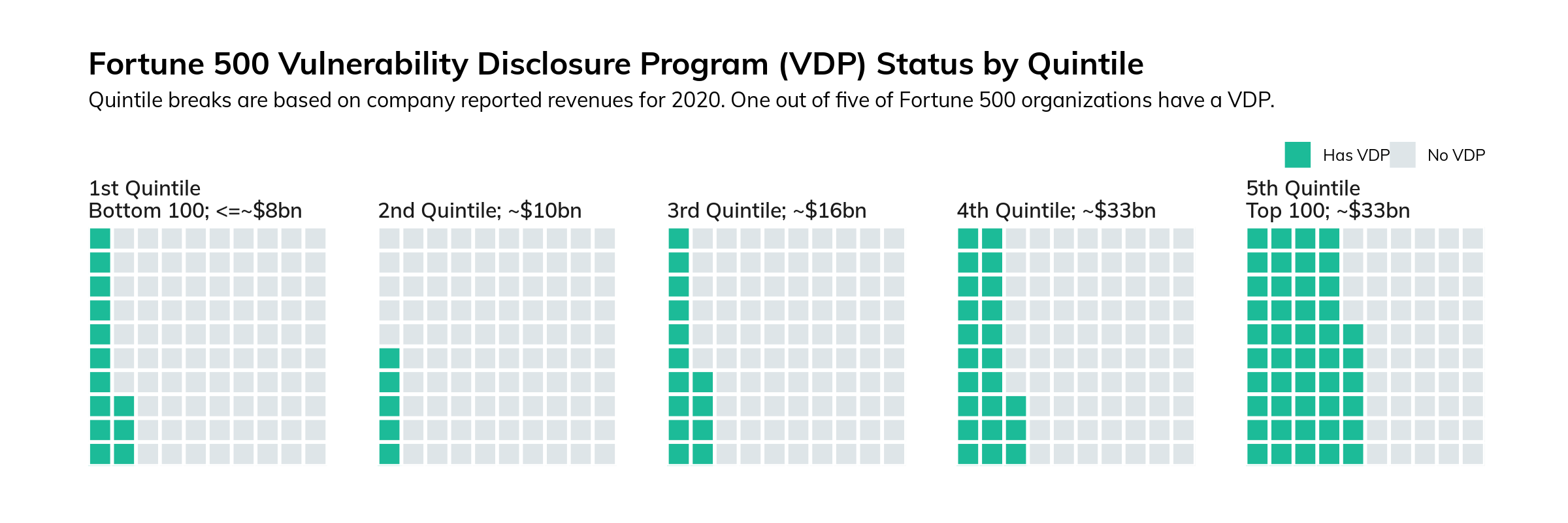

In January 2019, Casey Ellis, founder of Bugcrowd, remarked in a blog post that "only 9% of the Fortune 500 run vulnerability disclosure programs.” 34 Therefore, the most surprising finding in this 2021 survey is that nearly 20% of the Fortune 500 signal a VDP. We were able to discover 99 vulnerability disclosure programs across the 500 companies investigated in January 2021. Even more heartening is that among the top 100 companies, a whopping 46 have a documented, easily discoverable mechanism for reporting product or infrastructure vulnerabilities.

The most surprising finding in this 2021 survey is that nearly 20% of the Fortune 500 signal a VDP.

With that bit of good news out of the way, however, we must look at how the rest of the Fortune 500 fares. Figure 18 breaks the surveyed companies down into quintiles based on their reported revenues for 2020:

Figure 18

There is a marked drop-off in the presence of a VDP per quintile, except for the last quintile, where there's a marked increase again matching the third quintile. This rise in the first quintile may be partially explained by the fact that there are twice as many Technology sector companies in the bottom 100 as there are in the second quintile, and five out of 10 of those companies do have a VDP. In fact, as we'll see in the next section, Technology is the only sector in the Fortune 500 where the majority of companies have a VDP.

Figure 19 breaks down the Fortune 500 by industry, and demonstrates that, as one might expect, few industries outside of the technology sector have normalized and internalized vulnerability disclosure as a component of their businesses.

Figure 19

While the technology sector is unsurprisingly at the top of the list, the astute reader will note that this figure is sorted by percentage of companies within that industry that have a VDP, rather than by raw count. This is because the Fortune 500 is dominated by the financial sector—after all, that's where the money is (to borrow Sutton's Law), and it's no surprise that nearly one-fifth of the top-revenue companies in the United States are primarily engaged in financial services. So, while 21 financial services companies have a VDP, that is only 23% of all financials represented by the Fortune 500, which is nearly the same percentage as those found in the business services sector and somewhat less than the auto industry.

The key takeaway from this view of the Fortune 500 is that, while all major companies have some technical component (and therefore have technical vulnerabilities), nearly 80% of these top companies in the U.S. outside of the technology sector lack a formal vulnerability disclosure program. While this might be understandable in prior decades, this state of affairs is simply unacceptable in today's hyper-technical business environment.

Nearly 80% of these top companies in the U.S. outside of the technology sector lack a formal vulnerability disclosure program.

The lack of VDPs across the upper echelons of American economy discourages the reasonable and responsible disclosure of newly discovered vulnerabilities in their products, services, and infrastructure—after all, VDPs aren't just for reporting software bugs in software applications, but are also useful for reporting the discovery of sensitive data found about customers or company internals left open on insecure cloud storage. It is, of course, possible to disclose vulnerabilities to companies in industries without a formal VDP, but the lack of VDPs introduces inefficiencies for the companies and legal risk to researchers.

Finally, a functioning VDP signals that a given company has made some investment in their overall information security program, so it stands to reason that the lack of a VDP is signaling the opposite. Every company on this list has a website privacy policy, so every company should have some formal method for receiving and handling vulnerability reports.

CISO Takeaways

Hopefully, it is obvious by now that the authors of this paper are strong proponents of clearly defined, easily discoverable vulnerability disclosure programs. We believe that every company in the Fortune 500 (and beyond) should adopt one.

The authors of this paper are strong proponents of clearly defined, easily discoverable vulnerability disclosure programs. We believe that every company in the Fortune 500 (and beyond) should adopt one.

Launching and running a successful VDP may be tricky—after all, the presence of a VDP implies a level of security maturity that may not yet exist at a given company, so CISOs at organizations without a VDP are strongly encouraged to familiarize themselves with the basics of vulnerability disclosure.

We believe there is a critical mass of CISO expertise in building and maintaining VDPs that there is plenty of opportunity to learn from the experiences of others in the field. In our experience, not only do CISOs personally enjoy discussing their VDP experiences, but it can be hard to shut them up about it when they get going.

ISO 29147 35 (Information technology—Security techniques—Vulnerability disclosure) and ISO 30111 36 (Information technology—Security techniques—Vulnerability handling processes) are excellent starting points for building, maintaining, and improving a vulnerability disclosure program. These ISOs were developed in partnership with internationally recognized experts in the field of vulnerability disclosure, and can help any CISO get a leg up.

Another, first-step approach to establishing a minimal VDP is a contact and policy document placed at <hxxps://your-company.com/.well-known/security.txt>. This is a relatively new standard for VDP communication that provides for basic contact information signalling, readable by both humans and machines. 37

Conclusion

All in all, it should come as no surprise that that Fortune 500 cohort of companies are, broadly speaking, performing better at cybersecurity essentials as of early 2021. The global COVID-19 pandemic forced many of these companies to abruptly shift to a large work-from-home workforce in short order, and each company is its own miracle of corporate survival in the face of such drastic changes to the workplace.

That said, but more progress must be made, faster. The Fortune 500 employs over 28 million people and accounts for approximately two-thirds of the entire U.S. GDP. Because of their outsized position in the business community, they also tend to have access to the best and brightest cybersecurity experts from around the world, and so it is incumbent upon them to behave more like model internet citizens. The researchers at Rapid7 who contributed to this report sincerely hope that these companies—and the organizations that have business relationships with these companies—find this information and advice useful in our shared responsibility of advancing security for everyone.

CISO Actions At A Glance

Throughout this report, we've kept our focus on what CISOs in the Fortune 500 can do, today, to reduce their exposure to the most common issues we've discussed here. For the reader's convenience, those recommendations are summarized here.

Email Security: If you're on the Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting & Conformance (DMARC) path, like 75% of the Fortune 500, that's great! Now is the time to plan out how you'll move from a p=none to a p=quarantine policy, and ultimately a p=reject policy. This is not an easy journey, since you will certainly uncover pockets of shadow IT running their own email infrastructure, but the confidence of being able to authenticate mail from your major brand domains is a pretty great feeling, and a nice item to report to your board of directors.

Web Security: HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS) is rapidly becoming table stakes for running a reasonably secure website, and this is the kind of security feature that browser manufacturers like Google, Apple, Microsoft, and Mozilla are likely to enforce in future versions of Chrome, Safari, Edge, and Firefox. It's a relatively easy switch that CISOs can flick (compared to the universe of nice-to-haves in cybersecurity, anyway), so take some time to investigate whether your organization is using HSTS and if not, why.

Version Dispersion: For the mega-corporations that roam the fields of capitalism, mergers and acquisitions are a fairly common activity throughout the year. That means the Fortune 500 CISO is never truly "done" with ensuring version consistency across the enterprise, even after investing in an excellent asset and vulnerability management toolchain. New networks and network services will join your ranks, and that means undertaking a fairly continuous modernization and normalization effort for those new assets. Taking on this continuous effort will pay off in easier, more straightforward planning for the next patch cycle, scheduled or surprise.

High-Risk Services: Telnet, SMB, and RDP have no business being exposed directly to the world at large, and are just waiting for the next self-replicating cyberattack to sweep across the internet. An up-to-date inventory of exposed services, sourced from internal and external scanning, is worth its virtual weight in Bitcoin, and will help you enforce a no-nonsense policy of network service exposure to the internet.

Vulnerability Disclosure Programs: As a CISO, you might have hired on the best of the best software, QA, and platform engineers. But, without a good way to harness the smarts of the tens of thousands of talented hackers around the world, you may never learn about the most critical vulnerabilities in your products and services. A VDP is a bridge to that enormous community of well-meaning investigators who have goals aligned with your own: a safer and more secure internet. Getting that program spun up now will give you plenty of time to practice safer software production. As a bonus, most of the pioneering work is already done for you, in the form of ISO 29147 and ISO 30111.

Appendix: Prioritization in Times of Crisis

The disclosure of both the SolarWinds-related multiple-technology vulnerabilities (and associated campaigns), along with the release of the out-of-band Microsoft Exchange patches responding to active exploitation campaigns has strained virtually every single information security team in every industry. We wanted to take a moment to help ensure you're on safer ground, now, and also put each section into context relative to some of the crises we have already had to deal with this year.

The SolarWinds situation brought third-party risk square into focus like it has never been before. If you had a solid list of partners/vendors and a well-oiled contact plan (which many organizations did), you may have weathered that portion of the extended incident fairly well. If not, we hope you had the support required to put such things in place and have been able to use it in some subsequent serious vulnerability disclosures and exploit campaigns since.

When it comes to being able to get a feel for how well a partner/vendor values safety and resilience, you may want to heed the advice in the "CISO Takeaway" section. It's much easier to sleep at night knowing that the bulk of your third-party contacts prioritize email safety, avoid exposing dangerous services to the internet, and stay current with both patching and advanced encryption standards. You will also know how to contact them in the event you do discover a security issue with any of their products and services, since they'll have a vulnerability disclosure program in place.

Similarly, the massive Exchange vulnerability and associated malicious campaigns further demonstrated how quickly one weakness in a component used by hundreds of thousands of organizations can come out of the blue to disrupt execution on even the most well-crafted enterprise information security roadmap. Having current, accurate telemetry of what is deployed internally and externally along with highly agile quality assurance and change management processes (as noted in the section on version complexity) can be the difference in having an unexpected patch (like Exchange) be a quick exercise with a slight bit of triage (to ensure attackers did not have time to target you) vs. an "all hands on deck" massive incident.

We hope our quantification, context, and advice prove useful to you as you emerge from these two major incidents to take on the remaining challenges that await us all in 2021 and beyond.

1. https://www.rapid7.com/research/project-sonar

2. https://github.com/rapid7/recog

3. Common Platform Enumeration definition and database: https://nvd.nist.gov/products/cpe

4. A Cloud Native Computing Foundation 2019 survey notes 78% of respondents are using Kubernetes in production, a huge jump from 58% in 2018.

5. Kubernetes main site: https://kubernetes.io

6. Some organizations announce they use a particular server type but redact the discrete version number.

7. We frequently see leaking of IIS build strings in announced Server header banners in IIS deployments.

8. Microsoft 365/Office 365 adoption continues to grow at a significant clip, with 70% of the Fortune 500 using one or more services, including hosted Exchange. Source: https://www.thexyz.com/blog/microsoft-office-365-usage-statistics/

9. https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/exchange/new-features/build-numbers-and-release-dates

10. This does not take into account the fact that an organization may have a custom or extended support agreement with Microsoft, though that matters little when it comes to vulnerability exploitation.

11. https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/enterprise/exchange-2010-end-of-support?view=o365-worldwide

12. Yes, we took the obvious pun.

13. Perhaps Exchange 2010 is just pining for the fjords?

14. For free, even! https://opendata.rapid7.com/

15. https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/sysinternals/

16. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conficker

17. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WannaCry_ransomware_attack

18. https://wiki.wireshark.org/SMB2

19. Which now old enough to drive in most states (it was born in November 2006)

20. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telnet

21. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remote_Desktop_Protocol

22. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Network_Level_Authentication

23. https://www.rapid7.com/research/report/nicer-2020/#smb-tcp-445

25. https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/t5/storage-at-microsoft/stop-using-smb1/ba-p/425858

26. https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-server/storage/file-server/file-server-smb-overview

27. https://www.cisecurity.org/controls/cis-controls-list/

28. https://www.wsj.com/articles/every-company-is-now-a-tech-company-1543901207

29. https://blog.rapid7.com/2018/10/31/prioritizing-the-fundamentals-of-coordinated-vulnerability-disclosure/

30. https://blog.rapid7.com/2016/11/28/never-fear-vulnerability-disclosure-is-here/

31. https://www.bugcrowd.com/bug-bounty-list/

32. https://hackerone.com/directory/programs

33. https://github.com/disclose/diodb/

34. https://www.bugcrowd.com/blog/3-reasons-why-every-company-should-have-a-vdp/

35. https://www.iso.org/standard/72311.html

36. https://www.iso.org/standard/69725.html

37. Interested CISOs can read up on it at https://securitytxt.org/